Some plant compounds may complement prescription therapy. Quercetin and Metformin are often discussed together because their actions overlap in glucose and inflammation pathways. This article reviews how quercetin might support metformin, what foods contain it, and when to use caution. You will also find practical tips on supplements, interactions, and related options.

Key Takeaways

- Food-first strategy: Emphasize produce rich in quercetin for steady intake.

- Mechanistic overlap: Both agents influence glucose handling and cellular stress.

- Balanced expectations: Evidence is mixed; quercetin is not a drug.

- Safety matters: Review quercetin benefits and risks before adding supplements.

Understanding Quercetin and Metformin

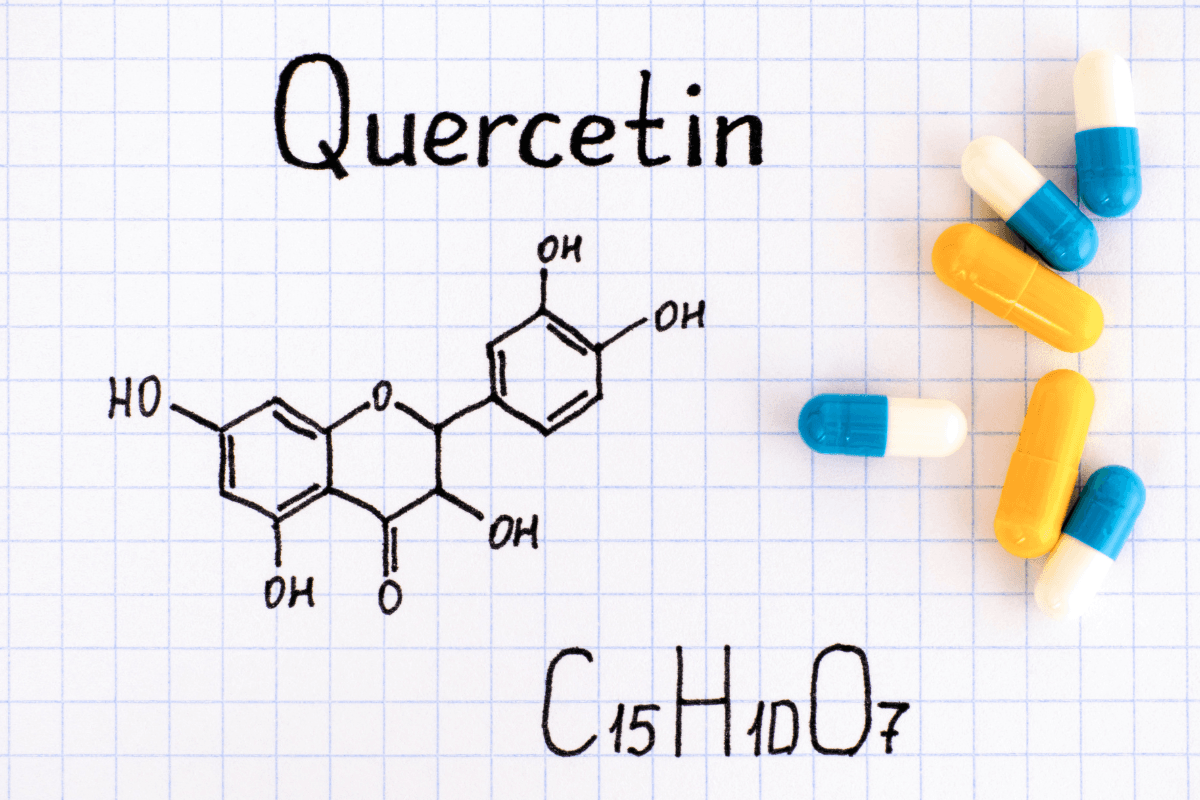

Quercetin is a polyphenolic flavonoid found in many fruits and vegetables. Clinically, it is studied for antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and metabolic effects. Metformin is a biguanide antihyperglycemic (glucose-lowering) medicine used as foundational therapy for type 2 diabetes. Together, these agents sit at the intersection of nutrition and pharmacotherapy.

Early and emerging research suggests overlapping actions. Quercetin may affect AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), oxidative stress, and intestinal glucose handling. Metformin’s benefits also involve AMPK activation and reduced hepatic glucose production. For a broader nutrition background on plant compounds and glycemic control, see Polyphenols and Diabetes for context on dietary polyphenols.

Mechanisms: How Quercetin Could Complement Metformin

Laboratory and small clinical studies indicate several plausible mechanisms. Quercetin can modulate enzymes and transporters related to carbohydrate digestion and absorption. It may also influence inflammatory signaling and endothelial function, which are relevant to cardiometabolic risk. These pathways could theoretically support metformin’s hepatic and peripheral glucose effects.

Evidence in humans remains heterogeneous across dose, formulation, and study length, so expectations should be modest. A frequent question is, does quercetin lower blood sugar? Some trials show small improvements in fasting glucose or insulin sensitivity, while others are neutral. For detailed background on metformin’s approved uses and mechanisms, review the FDA-approved labeling for metformin, which outlines its glucose-lowering actions.

Beyond glucose, anti-inflammatory actions may contribute to metabolic health. Readers interested in these pathways within drug therapy can see Metformin Combating Inflammation for an overview of inflammation-related mechanisms.

Quercetin in Foods and Daily Diet

Most people can obtain quercetin from a varied diet. Onions, capers, apples, berries, leafy greens, and herbs are notable sources. Cooking methods and food varieties change content, so rotating produce is helpful. A practical approach is to include one or two rich sources at most meals.

If you prefer simple grouping, think “alliums, apples, and leafy greens.” Alliums like red onions deliver significant amounts. Capers are exceptionally concentrated, but the serving sizes are small. Whole foods also add fiber, potassium, and additional polyphenols. For a more structured list, consult a quercetin foods chart or aim for the top ten foods high in quercetin within your usual cuisine. If you are adjusting fruit intake, see Grapes and Diabetes for context on fruit, sugars, and portions.

Tip: Keep a rotation list on your phone. Swap in-season options that fit your budget and taste.

People working on insulin resistance often pair dietary changes with activity. For pattern-based meal planning ideas, explore Best Diet for Insulin Resistance for practical food swaps and meal structure.

Diet-first strategies also align with long-term adherence. If you track intake, note servings that reliably include higher-quercetin items. Over weeks, this helps you evaluate whether consistent intake aligns with glycemic trends on your meter or CGM.

As a quick reference for shopping, mark produce sections where you find onions, kale, berries, and apples. These locations can act as cues for building balanced baskets around staples you already buy.

For quick readings on category-level nutrition topics relevant to diabetes self-management, browse the Diabetes articles library.

Supplements, Bromelain, and Practical Dosing

Some people consider a capsule when diet alone seems insufficient. When evaluating a quercetin supplement, check the labeled compound (e.g., quercetin dihydrate), dose per capsule, and any added ingredients. Products often pair this flavonoid with bromelain, an enzyme from pineapple stems, to potentially aid absorption or joint comfort. Evidence on the combination’s metabolic impact is still limited.

Pairings sometimes include vitamin C. The rationale is stability and potential synergy in antioxidant networks. However, formulations and bioavailability vary widely. If you are considering quercetin with bromelain, start with conservative expectations and review your medication list. To browse broad nutrition topics before selecting products, see the Vitamins and Supplements category for guidance-oriented content.

Dietary supplements are not regulated like prescription drugs. For general safety and labeling context on supplements, the NIH Office of Dietary Supplements offers a plain-language overview on how these products are overseen.

Safety, Interactions, and Who Should Avoid It

Like any bioactive compound, quercetin has potential downsides. The most commonly reported issues include gastrointestinal upset, headache, or tingling at higher doses. People on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy should be cautious because some laboratory data suggest effects on platelet function. Always review your medication list with a clinician or pharmacist.

Comorbid conditions matter. Thyroid disease, kidney impairment, or planned surgery may require additional precautions. Be alert to quercetin side effects if you experiment with new supplements, and stop use if you develop concerning symptoms. For a concise reference on diabetes drug tolerability, see Side Effects of Metformin to contrast supplement side effects with prescription experiences.

Quercetin may also interact with transporters and metabolizing enzymes that handle certain drugs. Space dosing several hours apart from other oral medicines if advised by your clinician. Monitor for unexpected changes in blood sugars if you start or stop supplements, and document patterns for discussion at your next appointment.

For consumer-level monograph details, the MedlinePlus page on quercetin provides a summary of uses, safety, and interaction considerations drawn from evidence reviews.

Cardiometabolic and Other Effects

Researchers have also explored blood pressure, lipids, and vascular function. A 2016 meta-analysis of randomized trials reported modest average reductions in blood pressure with supplemental quercetin, though effects varied by dose and duration. Study designs were short and heterogeneous, so individual responses may differ. Emerging data continue to refine these estimates.

People often ask, does quercetin lower blood pressure? It may offer a small reduction in some settings, but it is not a replacement for prescribed antihypertensives. For context on this evidence base, see a 2016 meta-analysis of trials summarizing blood pressure outcomes. Beyond the heart, dermatology studies suggest potential skin-calming effects in barrier stress, but findings are preliminary and not a substitute for standard care.

Weight, fitness, and glucose control also shape cardiometabolic risk. To learn how metformin may be used beyond classic diabetes indications, review Metformin Potential Uses for a survey of off-label research. Combine lifestyle strategies with medicines under clinician supervision for the best long-term outcomes.

Practical Guidance and Related Therapies

Integrating food sources is usually the safest starting point. If you are considering supplements, ask who should not take quercetin in the context of your diagnoses and medications. Keep a simple log of doses, timing, meals, and glucose readings for two to four weeks. Share the log at your next visit to discuss whether adjustments are sensible.

Combination diabetes therapies are common. To understand SGLT2 plus metformin options, see Invokana vs Metformin for comparative insights. For dual-agent tablets that include metformin, review Kazano Overview to see how combinations are structured.

Patients sometimes ask about extended-release forms for tolerability. For product-specific background on an extended-release formulation, see Glumetza for context on release profiles and dosing guidance from labeling. If your care team is considering an SGLT2-metformin fixed dose, Invokamet provides an example of combination therapy referenced in treatment plans.

If you are optimizing gut health alongside glucose management, see Probiotics and Type 2 Diabetes for microbiome-related considerations. For pregnancy-specific metformin topics, review Metformin Use During Pregnancy to understand risk–benefit discussions in that setting.

For ongoing reading within this topic area, browse Type 2 Diabetes to connect lifestyle insights with pharmacologic therapy. This can help you and your clinician align choices with personal goals and tolerability.

Recap

Quercetin from foods offers a practical, low-risk way to enrich a diabetes-friendly diet. Supplements may confer small benefits for a subset of people but should not replace prescribed therapy. Safety and interactions deserve attention, especially with complex medication lists. Use food-first strategies, monitor personal data, and discuss any additions with your healthcare team.

Note: Observational changes do not prove cause; decisions should weigh your clinical history, preferences, and the quality of evidence.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice.