Hyperkalemia is a common electrolyte disorder that needs careful evaluation. This guide explains what it is, how it affects the heart, and what steps clinicians may take to reduce risk.

Key Takeaways

- Definition and risks: High serum potassium can destabilize cardiac rhythm.

- Common drivers: Kidney disease, medications, acidosis, and tissue injury.

- Assessment: Symptoms, ECG, and labs guide urgency and treatment.

- Management: Stabilize the heart, shift potassium, and enhance removal.

What Is Hyperkalemia?

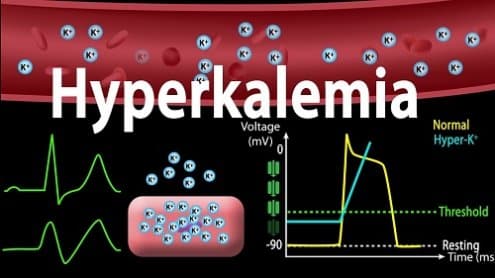

Clinically, this condition refers to an elevated serum potassium level above the normal reference range. Potassium helps regulate nerve conduction, muscle contraction, and membrane potential across tissues. Even small changes can affect myocardial excitability and conduction speed. Because disturbances may rapidly progress, clinicians combine symptom reports, lab trends, and electrocardiogram findings when judging severity.

Laboratory interpretation requires context. Hemolysis during blood draw, delayed sample processing, or severe leukocytosis can spuriously raise measured potassium (pseudohyperkalemia). Confirming an unexpected value with a repeat, non-hemolyzed sample is prudent before deep workups. Authoritative summaries on high potassium, including typical ranges and evaluation steps, are available in the MedlinePlus overview (MedlinePlus overview) and a StatPearls review (StatPearls review).

Signs and Symptoms

Many patients have no obvious complaints at first. When present, hyperkalemia symptoms can include muscle weakness, fatigue, tingling, or heaviness in the limbs. Some people notice palpitations, near-syncope, or chest discomfort. Symptoms alone cannot determine severity, so they are interpreted alongside ECG patterns and lab trends.

Neuromuscular effects range from subtle weakness to flaccid paralysis in advanced cases. Cardiac irritability can manifest as skipped beats or a slow, irregular pulse. If symptoms emerge after a medication change, dehydration, or an acute illness, clinicians usually reassess potassium, kidney function, and acid–base status to spot root causes and prevent recurrence.

ECG and Cardiac Effects

Electrocardiography helps detect conduction changes that may precede dangerous arrhythmias. A classic early finding is peaked T waves, often followed by PR prolongation, P-wave flattening, and QRS widening as levels rise. Documented patterns vary by patient and speed of onset. For clinicians, a concerning pattern plus an elevated level usually signals more urgent care, even if the person feels well.

In practice, a focused cardiac tracing can differentiate benign palpitations from an evolving conduction problem. The term hyperkalemia ecg usually references these hallmark changes that help guide immediate management. For a concise clinical reference on ECG changes and their implications, see the Merck Manual’s professional topic on high potassium (Merck Manual professional topic).

Causes and Risk Factors

Common causes of hyperkalemia include reduced kidney excretion, shifts of potassium from cells to blood, increased intake, and medication effects. Chronic kidney disease limits excretion capacity, so even moderate intake or minor dehydration can raise levels. Metabolic acidosis moves potassium out of cells, as can hyperglycemia or tissue breakdown from rhabdomyolysis or severe trauma.

Several drug classes can raise potassium by reducing renal excretion or altering hormonal pathways. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers support cardiovascular outcomes, yet they may elevate potassium in susceptible patients. For background on ACE inhibitors, see Benazepril Uses for kidney and heart benefits (Benazepril Uses). Finerenone also affects potassium handling; for cardiometabolic context, review Kerendia Uses and monitoring guidance (Kerendia Uses).

Special Considerations in Older Adults

Aging kidneys often have a lower glomerular filtration rate and less reserve, which reduces potassium excretion. Polypharmacy is common, and combinations such as an ACE inhibitor plus a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist can further increase risk. Intercurrent illnesses, dehydration, and poor oral intake may tip the balance. Clinicians usually review the medication list after any unexpected lab shift in seniors.

Diabetes, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease frequently cluster in older adults. Each condition can contribute to high potassium or complicate its management. For a deeper look at cardio-renal risk and potassium balance in diabetes-related kidney disease, see this overview on Diabetic Kidney Disease (Diabetic Kidney Disease). Broader renal topics are cataloged in our Nephrology articles collection (Nephrology) for additional context.

Classification and When to Act

Clinicians often classify levels into bands to guide urgency, from mild elevations to more severe ranges where arrhythmic risk rises. The term mild hyperkalemia generally refers to a small elevation above the upper limit of normal. Severity also depends on ECG changes, trend direction, comorbidities, and how quickly the level rose. A stable, low-level elevation in an otherwise well patient may warrant outpatient follow-up, while a rapid increase with ECG changes usually demands urgent care.

Professional guidance emphasizes individualized decisions that balance risk and benefit. For example, people with chronic kidney disease may have persistently higher baselines but remain stable with careful monitoring. Conversely, an acutely ill patient with widening QRS on ECG may need immediate stabilization. The National Kidney Foundation provides patient-friendly information on potassium in kidney disease that underscores monitoring and diet considerations (Kidney Foundation guidance).

Treatment Overview and Emergency Measures

Initial goals include stabilizing the myocardium, shifting potassium into cells, and enhancing elimination. Intravenous calcium (e.g., hyperkalemia treatment calcium gluconate) is commonly used to stabilize cardiac membranes when ECG changes are present. Temporizing intracellular shifts may follow, using approaches such as insulin with dextrose or inhaled beta-agonists, guided by clinician judgment and monitoring. Finally, elimination methods may include loop diuretics, potassium binders, or dialysis in selected scenarios.

Loop diuretics can increase urinary excretion when kidney function permits; for a product overview, see Lasix information and practical considerations (Lasix). Potassium binders help remove excess via the gastrointestinal tract; for details about a binder option, review Veltassa Sachet handling and administration notes (Veltassa Sachet). If metabolic acidosis contributes, addressing acid–base status may help; for mechanisms and causes, see Metabolic Acidosis Guide (Metabolic Acidosis Guide).

Diet and Lifestyle: Lowering Potassium Intake

Nutrition strategies can complement clinical treatment. People with kidney impairment may benefit from a tailored plan that moderates high-potassium foods while preserving overall nutrient quality. A dietitian can help translate lab goals into practical meals. If a clinician has advised restriction, reducing portion sizes of high-potassium fruits, legumes, and certain dairy products may lower daily intake without eliminating entire food groups.

Practical steps include choosing lower-potassium alternatives, soaking and boiling vegetables to reduce their content, and avoiding potassium-based salt substitutes. Read labels carefully on electrolyte drinks and supplements. Discuss any herbal products, as some contain added minerals. Consider this as part of a broader approach on how to lower potassium levels in coordination with the care team.

Practical Steps to Enhance Removal

Addressing contributors can improve control. Correcting constipation reduces colonic absorption time and may aid binder effectiveness. Hydration, when appropriate, supports renal perfusion; however, volume status must be individualized, especially in heart failure or advanced kidney disease. Reviewing the medication list and adjusting agents that raise potassium can significantly lower recurrence risk.

In certain cardiorenal conditions, additional therapies help the overall risk profile. For example, SGLT2 inhibitors may support kidney and heart outcomes; for drug class context, see this overview of SGLT2 Inhibitors (SGLT2 Inhibitors). If acid–base imbalance is present, treating the cause can assist potassium control; for background on detection and correction, refer back to the Metabolic Acidosis Guide (Metabolic Acidosis Guide). These steps align with a broader strategy on how to flush excess potassium safely.

Medications That Raise Potassium

Several agents increase potassium by reducing excretion or altering hormonal signaling. These include ACE inhibitors, ARBs, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, some immunosuppressants, and certain antifungals or antibiotics. Individual risk depends on kidney function, dose, and drug combinations. Regular monitoring helps balance therapeutic benefits with electrolyte safety.

For ACE inhibitor context and monitoring considerations, see How Altace Supports Heart Health (Altace Supports Heart Health) and Ramipril Uses and prevention of complications (Ramipril Uses). For ARB background, azilsartan is discussed in Edarbi resources and prescribing information. For nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism, review Kerendia Uses for indications and monitoring (Kerendia Uses).

Related Cardio-Renal Context

Electrolyte management intersects with broader cardiorenal care. Addressing albuminuria, blood pressure, and glucose control lowers the chance of rapid potassium shifts. If an ACE inhibitor is appropriate but potassium rises, clinicians may adjust dose, add a diuretic, or incorporate a binder. These choices weigh competing risks and the person’s overall cardiovascular profile.

For a broader look at medication classes that influence kidney and heart outcomes, see this primer on Benazepril Uses (Benazepril Uses) and a summary of SGLT2 Inhibitors for cardiorenal protection (SGLT2 Inhibitors). Category pages can also help you navigate related topics and products; explore Nephrology Products for formulary breadth and options (Nephrology Products).

Recap

High serum potassium can silently affect the heart before symptoms appear. A focused assessment—symptoms, ECG, and labs—helps determine urgency. Stabilizing the heart, shifting potassium intracellularly, and enhancing removal form the backbone of management. Long-term control depends on addressing causes and adjusting diet and medications responsibly.

With careful monitoring, most people achieve safe, steady potassium control. Coordination between primary care, cardiology, and nephrology improves outcomes, especially when multiple conditions and medications overlap. For additional renal topics, browse our Nephrology articles collection (Nephrology), which groups related content for easier review.

Note: External resources cited above offer accessible, authoritative summaries for further reading and shared decision-making.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice.