Key Takeaways

- Early clues matter: subtle vision changes often precede noticeable vision loss.

- Timely eye exams catch progressive damage before it threatens central sight.

- Treatment options include injections, laser, and surgery for advanced disease.

- Glycemic, blood pressure, and lipid control lower long-term risk.

Eye complications from diabetes progress quietly, then accelerate. Catching diabetic retinopathy early helps preserve reading, driving, and work function. Most people improve outcomes by combining regular eye exams with systemic control. For a broader context on retinal complications, see Diabetic Eye Disease for foundational definitions and pathways.

Diabetic retinopathy develops as high glucose injures retinal microvessels, leading to leakage, ischemia, and scarring. Over time, this damage can impair central and peripheral vision. Understanding the earliest symptoms, and when to seek evaluation, supports faster decisions and better care.

Diabetic Retinopathy Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms vary by severity and may fluctuate day to day. Early signs can include mild blur after meals, difficulty focusing at night, and momentary dark spots after near work. People sometimes notice colors looking washed out or less vibrant. These changes may come and go, which can delay concern.

As disease progresses, floaters (mobile dark specks), fluctuating blur, and areas of missing vision become more common. Sudden large floaters, a curtain over part of the vision, or a rapid drop in acuity may signal bleeding or retinal detachment. Prompt assessment is appropriate whenever a new, persistent change appears, especially after strenuous activity or a spike in glucose.

Common Visual Changes

Many patients report glare from headlights, longer adaptation when entering dim rooms, and intermittent double images that resolve with rest. Reading lines may seem wavy when macular edema develops. People who monitor carefully often notice that visual clarity tracks with glucose variability, blood pressure spikes, or missed antihypertensive doses. Tracking these patterns helps clinicians differentiate refractive shifts from retinal fluid or hemorrhage, guiding testing and treatment discussions.

Diabetic Eye Disease offers a concise overview of related conditions, which provides useful background for symptom comparisons.

Causes and Risk Factors

The primary drivers include chronic hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, and microvascular injury that disrupt the blood-retina barrier. Hypertension, kidney disease, and elevated lipids amplify leakage and ischemia. Duration of diabetes, pregnancy, and past poor control increase risk. Tobacco use and sleep apnea may worsen vascular instability, compounding progression.

Family history, anemia, and rapid correction of longstanding hyperglycemia can also contribute to short-term edema or hemorrhage. Addressing modifiable contributors supports care planning and lowers the chance of vision-threatening events. For clarity on etiology and mechanisms, the phrase diabetic retinopathy causes summarizes this multifactorial pathway.

Stages and Early Eye Changes

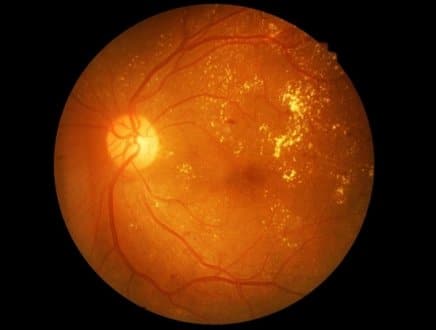

Clinicians classify disease by nonproliferative stages (mild, moderate, severe) and the proliferative phase. Early microaneurysms, dot-blot hemorrhages, and hard exudates characterize nonproliferative disease. Macular edema may occur at any stage and often explains central blur or metamorphopsia. Severe nonproliferative disease reflects extensive ischemia and higher short-term risk.

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy represents abnormal neovascular growth, which can bleed or pull the retina. New vessels on the disc or elsewhere predict vitreous hemorrhage or tractional detachment. Recognizing early ischemic signs, such as numerous cotton-wool spots or venous beading, helps anticipate progression and plan timely intervention.

For prevention strategies tied to retinopathy burden, see Managing Retinopathy in Diabetes, which outlines control targets and visit timing.

Diagnosis and Screening

Evaluation includes dilated fundus examination, optical coherence tomography (OCT) for macular edema, and fluorescein angiography when ischemia or neovascularization is suspected. Fundus photography documents baseline status and supports teleophthalmology triage. Primary care teams can coordinate referrals when visual changes persist or screening is overdue.

People often ask, what is the first sign of diabetic retinopathy. The most consistent early finding is a tiny retinal microaneurysm that may not alter vision. Practical screening intervals are advised by the AAO guidance, and systemic targets are defined in the ADA Standards of Care. For how broader diabetes control supports eye health, see How Diabetes Affects Eyes as a practical explainer.

Treatment Options

Care plans depend on stage, the presence of macular edema, and overall health. Observation with close follow-up may suit mild, stable findings. When edema impairs central vision, anti-VEGF injections or focal/grid laser may help reduce fluid and improve clarity. Panretinal photocoagulation helps regress neovascularization and reduce bleeding risk.

Anti-VEGF therapy is a first-line approach for center-involving edema. To learn about specific agents used in the retina clinic, see Eylea for aflibercept indications, and Beovu Pre Filled Syringe for brolucizumab details; both links provide product profiles for context. Corticosteroid options may be considered when inflammation or VEGF-independent pathways dominate; Triesence serves as a reference example for triamcinolone acetonide.

When comparing modalities, the NEI overview summarizes evidence for injections and laser. Discussions typically weigh clinic visit frequency, systemic comorbidities, and response to prior therapy. Shared decision-making helps align visual goals with treatment burden.

People often search for diabetic retinopathy treatment to better understand when escalation is needed and what to expect at the visit.

Surgery and Recovery

Pars plana vitrectomy is considered when dense vitreous hemorrhage persists, tractional retinal detachment threatens the macula, or fibrovascular scarring distorts the retina. Intraoperative choices may include membrane peeling and endolaser to address ischemic areas. Gas or oil tamponade can be used when detachment repair is required.

Expect activity restrictions based on tamponade choice, underlying comorbidities, and surgeon protocol. Discuss travel, sleep positioning, and return-to-work needs ahead of time. Understanding diabetic retinopathy surgery recovery time helps patients plan transportation, caregiver support, and follow-up schedules without surprises.

Medication and Eye Drops

Systemic optimization remains the bedrock: glucose, blood pressure, and lipids. In the eye, steroid implants or periocular injections may help selected cases of refractory edema. Topical therapies do not treat retinal ischemia directly, but they may support coexisting ocular hypertension or surface disease that complicates imaging and recovery.

When glaucoma overlaps, topical choices are tailored to the optic nerve and corneal health. Examples include Dorzolamide Ophthalmic Solution or Timolol to lower intraocular pressure, and fixed combinations like Cosopt. Prostaglandin-related options, such as Vyzulta Ophthalmic Solution, may be considered when ocular surface tolerance allows. Discussing diabetic retinopathy medication choices in context helps avoid conflicts with systemic conditions.

Prognosis and Prevention

Outcomes improve with timely detection and consistent follow-up. Many people maintain driving-level vision with modern care. Strong A1C control, stable blood pressure, and statin therapy where indicated reduce progression risk. Lifestyle measures, including sleep and smoking cessation, support vascular health.

While established scarring does not vanish, edema and neovascularization often regress with treatment. In practical terms, can diabetic retinopathy be reversed depends on the feature: fluid and new vessels can improve, whereas ischemic scarring does not. For self-care routines that protect long-term sight, see Promote Eye Health Amidst Diabetes for daily habits that support healthier eyes.

Coding and Documentation

Accurate coding distinguishes nonproliferative from proliferative disease and notes macular edema. Laterality, diabetes type, and complication presence guide code selection. Documentation should include imaging summaries, treatment plans, and comorbidity management, enabling consistent follow-up scheduling and clear communication across teams.

Clinics often streamline templates for stage, edema status, and treatment intent. Including systemic metrics like recent A1C, blood pressure, and lipid profile supports integrated care and quality reporting. Clear coding also helps align referral urgency and triage for teleophthalmology workflows.

Costs and Access

Costs vary by region, drug selection, and visit frequency. Insurance coverage, co-pays, and assistance programs can influence therapy choice and adherence. Discussing anticipated visit cadence and imaging needs helps patients plan budgets and transportation early.

Community programs and bundled visits can reduce burden for those traveling long distances. Multidisciplinary coordination between endocrinology, primary care, and ophthalmology often limits redundant testing, improving both cost and convenience. For ongoing education across conditions, browse the Diabetes and Ophthalmology article categories for broader context.

Recap

Vision changes from retinal disease often start subtly, then advance faster. Early detection, systemic control, and timely procedures offer the best chance to preserve daily function. Pair scheduled eye exams with steady glucose, blood pressure, and lipid targets. Use clear documentation and coordinated care to maintain momentum.

Note: External resources in this article reflect consensus guidance and may evolve with new evidence.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice.