Clear distinctions help everyday decisions. Understanding type 1 vs type 2 diabetes improves conversations with your care team and guides safer self-management at home.

Key Takeaways

- Core cause difference: autoimmune loss of insulin vs insulin resistance.

- Onset patterns differ, but overlap; tests confirm the diagnosis.

- Glucose targets are similar; monitoring needs can vary.

- Treatment intensity ranges from lifestyle to basal–bolus insulin.

- Complication risks depend on duration, control, and comorbidities.

Type 1 vs Type 2 Diabetes: Key Differences

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune condition where the immune system destroys pancreatic beta cells. Insulin production falls sharply, creating absolute deficiency. Type 2 diabetes involves insulin resistance and a gradual decline in beta-cell function over time. Many people start with adequate insulin, but the hormone cannot work effectively at target tissues. Why this matters: the biological driver shapes testing, medication choices, and education.

Although textbooks contrast childhood-onset type 1 with adult-onset type 2, real-world presentations overlap. Adults can develop autoimmune diabetes, and youth may have insulin-resistant type 2, especially with obesity or family history. Because misclassification delays proper therapy, clinicians often use antibody testing and C‑peptide to clarify the type. For deeper mechanism context, see Insulin Resistance vs Insulin Deficiency for a concise comparison of pathways.

| Feature | Type 1 | Type 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Driver | Autoimmune beta-cell loss | Insulin resistance ± beta-cell decline |

| Typical Onset | Rapid (days–weeks) | Gradual (months–years) |

| Body Weight | Any, often lean/normal | Any, often overweight |

| Insulin at Diagnosis | Usually required | Not always required |

| Autoantibodies | Often present | Usually absent |

Causes and Risk Factors

Type 1 is driven by autoimmunity with genetic and environmental inputs. Common antibodies include GAD65, IA-2, and ZnT8. Triggers may include viral exposures and other immune stressors. Family history raises risk but does not guarantee disease. In contrast, type 2 reflects a mix of genetics, age, reduced physical activity, and adiposity distribution, especially visceral fat. Over time, pancreatic beta cells can fatigue, lowering endogenous insulin output.

Public health and clinical literature discuss what causes type 2 diabetes as a combination of insulin resistance, impaired incretin signalling, hepatic glucose output, and chronic inflammation. Risk increases with advancing age, metabolic syndrome, and certain ethnic backgrounds. Weight gain is not the only factor; sleep apnea, glucocorticoid use, and polycystic ovary syndrome also contribute. For medication overview by mechanism, see Diabetes Medications and How They Work to connect drug classes with these pathways.

Symptoms and Onset Patterns

Rapidly rising glucose in type 1 may cause thirst, frequent urination, unintended weight loss, fatigue, and blurry vision over days or weeks. Without insulin, ketones can accumulate, increasing the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis. By contrast, type 2 often develops silently. People may notice mild fatigue or gradual weight changes for months before diagnosis is made through screening or routine labs.

When comparing type 1 vs type 2 diabetes symptoms, overlap is common at high glucose levels. Recurrent infections, slow-healing wounds, and neuropathic tingling can occur with sustained hyperglycemia in either type. Sudden nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain suggest ketosis and need urgent evaluation. For patient-friendly comparisons of basal and bolus regimens, review Tresiba vs Lantus for basal options and Humulin vs Humalog for rapid-acting differences.

Diagnosis and Confirmatory Tests

Clinicians confirm diabetes using fasting plasma glucose, A1C, or oral glucose tolerance testing, then determine the likely type. In practice, how to diagnose type 1 diabetes vs type 2 involves integrating age, body habitus, family history, ketosis risk, and medication response. If uncertainty remains, antibody panels and C‑peptide testing help clarify endogenous insulin capacity. Making the correct call guides therapy intensity and education needs.

When classification is unclear, a test to differentiate type 1 and 2 diabetes may include GAD65 and ZnT8 antibodies plus C‑peptide with a concurrent glucose level. Low or absent C‑peptide suggests absolute deficiency. Rechecking after glucose stabilization can improve accuracy. For device and delivery considerations, see Insulin Pen vs Syringe to match tools with treatment plans.

Diagnostic thresholds and testing guidance are maintained by expert bodies. For current criteria and population screening advice, review the CDC testing overview for accessible standards and the NIDDK diabetes primer for clinician-focused detail.

Blood Glucose Targets and Monitoring

Day-to-day targets are similar across types unless individualized for age, comorbidities, or hypoglycemia risk. Many adults track fasting and post-meal values and review A1C every few months. Practical ranges help people interpret meters and CGMs. Providers often share a chart of typical targets and explain pattern management, sick-day adjustments, and exercise effects. Understanding normal blood sugar levels for adults supports safer dosing and timely diet changes.

Glycemic cutoffs used at diagnosis differ from ongoing goals. A clinician may discuss the type 2 diabetes range at diagnosis while setting individualized targets going forward. CGM trend arrows, overnight basal checks, and post-exercise monitoring all refine day-to-day care. For a deeper dive into storage and usage of long-acting insulin, see Lantus Vial for practical handling guidance and Insulin Pen Needles for selection and technique tips.

Treatment Paths and Self-Management

Type 1 requires exogenous insulin because the pancreas produces too little or none. Many use basal–bolus regimens with pens or pumps, plus rapid-acting corrections. Education covers carbohydrate counting, correction factors, and ketone checks during illness. In type 2, therapy usually starts with lifestyle measures and oral agents; insulin may be added when beta-cell function declines or when glucose is very high at diagnosis. These paths are flexible and adapt to individual goals and risks.

People often ask which diabetes is insulin-dependent; the answer is type 1 by definition, but some with type 2 benefit from insulin during illness, pregnancy, or advanced disease. Device choices also matter. If rapid mealtime control is needed, options like the Humalog KwikPen can be discussed with a clinician for suitability. For steady background coverage, a basal option such as the Lantus Vial may be considered as part of a comprehensive plan.

Choosing among therapies requires understanding pros and cons. To compare basal insulins for stability and flexibility, see Tresiba vs Lantus for dosing background and Diabetes Medications and How They Work for non-insulin options like metformin and SGLT2s. For cost-saving strategies across therapies, the guide Cut Insulin Costs outlines practical steps to discuss with your pharmacist.

Complications, Risks, and Prevention

Complication risk stems mainly from duration of diabetes and glycemic exposure, alongside blood pressure, lipids, and smoking status. Both types can lead to retinopathy, kidney disease, and neuropathy. Early detection and sustained risk-factor control help most. Annual eye exams, kidney checks, and foot assessments are standard recommendations. For eye health context and prevention tips, see Diabetic Eye Disease for warning signs and protective habits.

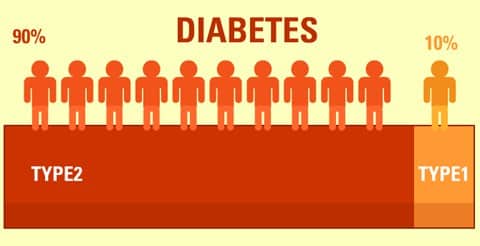

People often wonder which is worse, type 1 or 2; the reality is nuanced. Severe hypoglycemia and ketoacidosis are more common in type 1, while cardiovascular disease burdens many with type 2. Population statistics vary by region; in the U.S., type 1 represents a smaller share of total cases. For broad epidemiology and global perspective, review the CDC statistics report and this WHO fact sheet for international trends and definitions.

Tip: Build prevention habits early. Balanced nutrition, regular activity, and blood pressure and lipid control reduce complications in both types and support better day-to-day energy.

Recap

Type 1 centers on immune-mediated insulin deficiency; type 2 centers on resistance with gradual beta-cell decline. Onset, testing, and treatment paths differ, yet glucose targets and complication prevention strategies largely overlap. Matching therapy to biology, monitoring patterns, and personal goals helps ensure safer outcomes.

For practical comparisons across tools and therapies, explore Insulin Pen Needles for technique, and Insulin Resistance vs Insulin Deficiency for mechanisms that shape treatment decisions.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice.