The diabetes and endocrine system connection explains why blood glucose rises, falls, and sometimes stays stubbornly high. Hormones regulate energy use, organ communication, and stress responses. When insulin signaling fails, other glands compensate, often in ways that worsen hyperglycemia. Understanding these loops helps you interpret symptoms, labs, and treatment choices.

Key Takeaways

- Hormone network basics: Pancreas, thyroid, adrenals, gut, and brain coordinate glucose.

- Type distinctions: Autoimmunity drives Type 1, while resistance drives Type 2.

- System-wide effects: Nerves and digestion often change with chronic hyperglycemia.

- Care approach: Pair lifestyle, medications, and timely specialist referral.

Diabetes and Endocrine System

Diabetes sits within the larger hormone network that keeps internal balance (homeostasis). The pancreas releases insulin and glucagon to stabilize glucose. The adrenal glands add cortisol and adrenaline during stress. The thyroid tunes metabolic rate, while gut hormones signal after meals. When glucose remains high, counter-regulatory signals may intensify, making control harder.

Clinicians consider both the immediate glucose snapshot and the background endocrine milieu. Sleep loss, infection, thyroid status, and medications can shift hormone output. That is why the same meal might raise glucose one day and not the next. A structured review of symptoms, labs, and drugs can uncover hidden endocrine drivers.

What Is the Endocrine System?

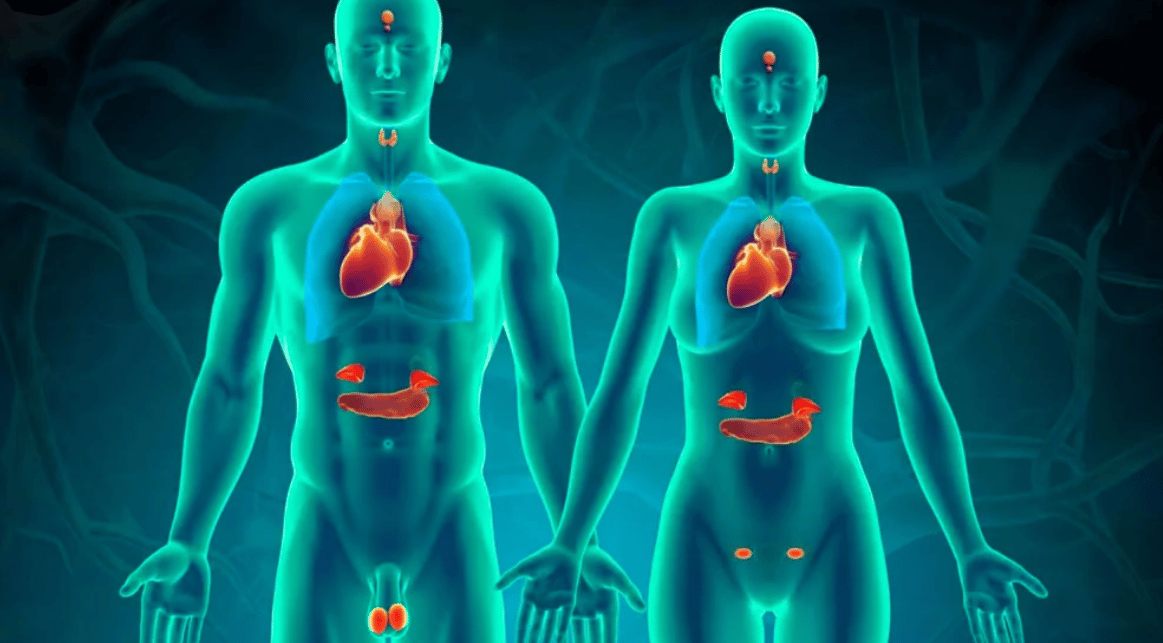

In plain terms, the endocrine system is a network of glands that release chemical messengers into the blood. These messengers are hormones, and they act on distant organs. Key players include the pituitary, thyroid, parathyroids, pancreas, adrenals, ovaries, and testes. Signals move in feedback loops, tightening or loosening hormone output as conditions change.

For a concise overview of glands and hormones, see the MedlinePlus endocrine overview (authoritative patient-friendly summary) here. The question of what is the endocrine system matters because disruptions of one gland often ripple across others. A clear mental model helps relate symptoms, such as fatigue or weight changes, to hormone patterns.

How Diabetes Disrupts Hormones and Feedback Loops

High glucose alters the usual balance between insulin and glucagon. In insulin deficiency or resistance, alpha cells may release more glucagon, further raising glucose. Stress pathways add cortisol and catecholamines, which increase hepatic glucose output. Over time, this can reset set-points and blunt post-meal satiety signaling from gut incretins.

For treatment fundamentals and medicine classes, the NIDDK insulin basics provides a neutral overview; review it on the NIDDK site. Clinically, the key question is how does diabetes affect the endocrine system in a given person. Look for patterns in fasting versus post-prandial glucose, signs of cortisol excess, and thyroid shifts that might explain variability.

Type 1 vs. Type 2: Endocrine Pathways

Type 1 diabetes stems from autoimmune beta-cell destruction, leading to absolute insulin deficiency. C-peptide levels often fall to very low or undetectable ranges. Autoantibodies may be present, and onset can be rapid. Early insulin therapy becomes essential to restore basal and bolus coverage and prevent ketosis.

In contrast, Type 2 starts with insulin resistance and progressive beta-cell stress. Weight gain, sleep disruption, and genetics increase risk. Over time, insulin output can decline, narrowing options. When discussing type 1 diabetes, also revisit anatomy. For a pancreas refresher, see Organ that Produces Insulin for concise context and diagrams, via Organ that Produces Insulin.

Is Diabetes an Endocrine or Metabolic Disorder?

Diabetes is both. It is endocrine because it involves a hormone (insulin) and its receptors, and it is metabolic because it changes how cells use glucose, lipids, and proteins. The practical framing depends on the clinical question. If you are sizing hormone deficits, endocrine thinking helps. If you are addressing fuel use and weight regulation, metabolic framing helps.

Clinicians often ask, is diabetes an endocrine disorder, to orient testing and referrals. A workable approach is to assess endocrine status (thyroid, adrenal, gonadal) when symptoms point that way or glucose remains unstable. For broader topic context across comorbidities and therapies, scan our Diabetes Articles collection.

Common Endocrine Disorders Overlapping with Diabetes

Thyroid disease, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and Cushing syndrome commonly co-occur with diabetes. Hypothyroidism can slow gastric emptying and raise LDL cholesterol, complicating risk management. Hyperthyroidism may worsen hyperglycemia by increasing hepatic glucose output. PCOS features insulin resistance and androgen excess, often with irregular menses and weight gain.

In many clinics, the most common endocrine disease documented is diabetes, closely followed by thyroid disorders. When hypothyroidism is confirmed, levothyroxine may be needed. For product details on dosing forms, see Synthroid for thyroid replacement context. For syndrome interplay and weight concerns in reproductive-age patients, review PCOS and Diabetes to understand bidirectional risks.

Diabetes Insipidus and Water Balance

Diabetes insipidus (DI) is distinct from diabetes mellitus. DI involves impaired vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone) signaling, causing large volumes of dilute urine and intense thirst. Central DI reflects hormone deficiency. Nephrogenic DI reflects renal resistance despite normal hormone levels. Serum sodium may rise if intake cannot keep up with losses.

Because DI affects fluid regulation rather than sugar, its evaluation centers on water-deprivation testing, plasma sodium, and urine osmolality. Clinicians often ask whether is diabetes insipidus an endocrine disorder. It is, because vasopressin release and action are endocrine functions. Clear differentiation prevents misdirected glucose therapies for a water-balance problem.

Insulin and Other Hormones

Insulin is the primary anabolic signal for glucose uptake. Skeletal muscle and adipose tissue depend on it to move glucose from blood to cells. Counter-regulatory hormones include glucagon, cortisol, growth hormone, and catecholamines. Incretin hormones from the gut modulate post-meal insulin release and satiety.

A common teaching point is: is insulin a hormone. Yes, it is a peptide hormone produced by pancreatic beta cells. For physiology background, see the Function of Insulin explainer. To locate its source and islet structure, see Where Is Insulin Produced for an anatomical refresher and lab relevance.

Nervous and Digestive System Effects

Long-standing hyperglycemia can injure peripheral nerves and the autonomic nervous system (the automatic control network). Symptoms include numbness, burning pain, dizziness on standing, and altered sweating. Gastroparesis may cause early satiety, reflux, or erratic post-meal glucose. These patterns complicate dose timing and meal planning.

For an evidence-based summary of nerve damage patterns, see the NIDDK neuropathy guide on this page. GLP-1 receptor agonists slow gastric emptying, sometimes unmasking underlying motility issues. For broader context on these medicines, review GLP-1 Weight Loss Drugs to understand their gastrointestinal effects and benefits.

Screening, Monitoring, and When to Refer

Start with a structured history, then target labs. Core tests include fasting glucose, A1c, lipid profile, TSH, and when indicated, morning cortisol or prolactin. Consider celiac screening in suspected autoimmune clusters. Autonomic symptoms justify orthostatic vitals and, when available, gastric emptying studies. Persistent unexplained hypoglycemia warrants review of adrenal function and medication lists.

Early referral to endocrinology helps when glucose remains unstable despite stepwise therapy, when autoimmune features are suspected, or when multiple gland systems appear involved. For delivery devices and formulation details that influence dosing practicality, see Insulin Cartridges for types and usage considerations. For technology-assisted management, the Artificial Pancreas Trial article summarizes closed-loop developments.

Treatment Principles and Team-Based Care

Ground care in nutrition, activity, sleep, and stress strategies. Then layer medicines to match physiology. Metformin reduces hepatic glucose output. GLP-1 receptor agonists support satiety and may aid weight management. SGLT2 inhibitors increase urinary glucose excretion and may support cardio-renal outcomes. Basal-bolus or pump insulin addresses absolute or advanced beta-cell failure.

For a product overview of a GLP-1 option used in Type 2 care, see Ozempic Pens to understand formulation aspects. For regulatory and practice updates on oral semaglutide, read Rybelsus First-Line and the broader Mounjaro Heart Benefits discussions for risk-profile context. Note: Medication selection should align with individual risk, comorbidities, and clinician judgment.

Recap

Diabetes is best understood as an endocrine and metabolic condition acting across systems. The pancreas, gut, thyroid, adrenals, and brain coordinate energy use and stress responses. When insulin falters, compensating hormones can deepen dysglycemia. Clear testing plans and multidisciplinary care reduce confusion and improve stability.

For thyroid-focused topics, scan our Endocrine Thyroid category to connect gland dysfunction with glucose patterns. For related comorbidities, therapies, and technology updates, visit the curated Diabetes Articles hub for structured reading and deeper dives. For an overview of evidence-based hormone care, ADA and NIH resources offer neutral summaries of mechanisms and monitoring recommendations.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice.