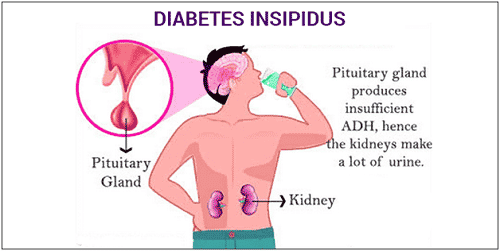

Central diabetes insipidus is a water-balance disorder caused by reduced vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone) signaling. People pass large volumes of dilute urine and feel constantly thirsty. This guide explains causes, testing, treatment, and safety basics in clear terms.

Key Takeaways

- Water-balance disorder: impaired vasopressin leads to excessive urination.

- Core workup: serum sodium, osmolality, and urine studies guide diagnosis.

- Main therapy: desmopressin plus individualized fluid strategies.

- Safety focus: avoid dehydration and treatment-related hyponatremia.

- Differentials matter: distinguish from nephrogenic DI and SIADH.

Understanding Central Diabetes Insipidus

In this neuroendocrine condition, the hypothalamus or posterior pituitary fails to produce or release adequate vasopressin. Without vasopressin, kidneys cannot concentrate urine, so water is lost rapidly. Patients often void more than 3 liters daily, sometimes far more. Thirst becomes an essential defense against dehydration, especially in warm environments or during illness.

Clinicians may use the term neurogenic to emphasize the central origin of the defect. Causes range from idiopathic to structural brain disease. For broad patient-friendly background, see the concise NIDDK overview, which outlines mechanisms and care basics. For a general orientation to symptoms and care steps across types, the Signs and Treatment Overview offers practical context that complements this page.

Causes and Risk Factors

Damage to the hypothalamus or posterior pituitary is the usual driver. Common sources include traumatic brain injury, pituitary surgery, craniopharyngioma, germinoma, metastases, and inflammatory diseases such as lymphocytic hypophysitis. Infections (for example, meningitis), ischemia, and radiation therapy can also impair vasopressin neurons. A subset of cases remain idiopathic despite imaging and serologic evaluation.

Genetic forms involve AVP gene variants and may present in childhood. Pregnancy can unmask or worsen symptoms due to increased vasopressinase. As a contrast point, lithium therapy can blunt renal response to vasopressin and cause nephrogenic diabetes insipidus; clinicians often consider nephrogenic diabetes insipidus lithium when polyuria emerges in patients receiving mood stabilizers. For renal-cause specifics and care nuances, see Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus, which expands on mechanism and management differences.

Symptoms and Daily Impact

Polyuria (frequent, large-volume urination) and polydipsia (intense thirst) dominate. Nocturia fragments sleep and may cause fatigue, headaches, or trouble concentrating. Dry mouth, cramps, and lightheadedness can signal underhydration. In hot weather or during strenuous activity, fluid needs can rise quickly, creating safety concerns.

Adults commonly describe planning their day around restroom access and water availability. Work, travel, and social events require forethought. The pattern and severity of diabetes insipidus symptoms in adults vary with residual vasopressin function, behavior, and environment. Alcohol suppresses vasopressin and may amplify urine output; for practical considerations, see Diabetes Insipidus and Alcohol for interaction insights and moderation tips.

Diagnosis and Testing

Initial evaluation documents hypotonic polyuria, typically with 24-hour urine volume and urine osmolality. Serum sodium and plasma osmolality help establish a water-balance pattern. High-normal to elevated values suggest water loss outpacing intake. Urine specific gravity remains low despite dehydration pressure. This laboratory pattern steers the clinician toward formal testing.

Where appropriate expertise exists, the classic deprivation protocol can clarify mechanism. In many centers, the combined approach—water restriction, vasopressin analog response, and sometimes copeptin assays—defines type and severity. Clinicians may reference the central vs nephrogenic diabetes insipidus water deprivation test when discussing how urine concentration changes after desmopressin. For help distinguishing sugar diabetes from water-balance disorders, see Diabetes Mellitus vs Insipidus, which outlines naming, lab markers, and treatment contrasts. For more technical background, the Merck Manual professional review summarizes diagnostic algorithms and test caveats.

Treatment and Long-Term Care

Therapy centers on replacing the missing hormone signal and aligning fluid intake with physiological needs. Desmopressin, a synthetic vasopressin analog, reduces urine output and improves sleep and quality of life. Formulations include intranasal and oral options. Dosing is individualized to avoid overcorrection. Education on thirst cues, sick-day rules, and travel preparation improves safety and consistency of care.

Guideline themes emphasize symptom control, electrolyte monitoring, and patient education. Many clinicians discuss central diabetes insipidus treatment as a balance between adequate control and avoiding water retention. Hyponatremia can occur if desmopressin use outpaces free-water excretion. For safety language and contraindications, consult the FDA desmopressin label, which details risks and monitoring points. For downstream risks and prevention strategies, review Complications of Diabetes Insipidus to understand electrolyte and kidney considerations.

Complications and Safety Considerations

The main risks arise from under- or over-replacement. Too little fluid or missed doses can allow dehydration and hypernatremia, presenting with thirst, weakness, and confusion. Conversely, excessive fluid intake with continuous desmopressin can lower sodium to dangerous levels. Early recognition of cognitive changes, nausea, or seizures requires urgent care.

Clinicians monitor the diabetes insipidus sodium level to ensure safe therapy. During intercurrent illness, vomiting or diarrhea can unmask vulnerability; temporary dose adjustments may be required under clinical supervision. Patients often carry a medication list and an emergency plan. For ongoing learning and related topics, browse Endocrine & Thyroid Articles, which aggregates hormone-disorder content relevant to water balance and pituitary function.

How It Differs: Nephrogenic DI and SIADH

Central DI reflects insufficient vasopressin signal; nephrogenic DI reflects renal resistance to a normal signal. Drug exposures, particularly lithium, and inherited collecting-duct defects drive renal resistance. Serum sodium often rises without adequate intake in both forms, but pharmacologic responses diverge. Imaging and history also differ, guiding targeted therapy and prevention.

SIADH sits at the opposite end of water balance, with excess antidiuretic effect and inappropriately concentrated urine. Low sodium is common, and fluid strategies contrast sharply. Clinicians often frame the distinction as central diabetes insipidus vs siadh when considering lab triads and volume status. For renal-resistance specifics and therapies, see Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus for mechanisms, medications, and follow-up needs. For product navigation by endocrine category, browse Endocrine & Thyroid Products if you need device or supply context.

Living With a Rare Water-Balance Disorder

Planning ahead reduces stress. Keep desmopressin accessible, carry water, and identify restrooms on new routes. Share a brief explanation with coworkers or teachers. On long flights, pack extra doses and a small container for measured fluids. Wear a medical alert if you have severe disease or limited thirst perception.

Track urine patterns and thirst to notice over- or under-control trends. Changes in work hours, heat exposure, or exercise may warrant temporary adjustments directed by your clinician. Alcohol and caffeine can complicate fluid control; for evidence-informed context, see Diabetes Insipidus and Alcohol, which explains why moderation matters. If you are comparing water-balance disorders to blood-sugar conditions, note that therapies such as Rybelsus Semaglutide Pills treat type 2 diabetes mellitus and highlight the very different treatment goals.

Recap

Central DI arises from reduced vasopressin signaling, causing dilute polyuria and thirst. Diagnosis relies on targeted labs and, when needed, structured testing. Desmopressin and fluid strategies control symptoms, while sodium monitoring protects safety. Clear differentiation from nephrogenic DI and SIADH prevents missteps and guides long-term care.

Note: For deeper background across endocrine topics related to pituitary and fluid balance, explore curated pieces under Endocrine & Thyroid Articles for context and further reading.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice.