Key Takeaways

- Transformative breakthrough: Insulin turned fatal diabetes into a manageable condition.

- Shared credit: Discovery involved Banting, Best, Macleod, and Collip.

- Modern production: Recombinant DNA methods now supply consistent insulin.

- Continuing evolution: New analogs and delivery tools improve daily use.

Understanding the discovery of insulin helps explain how diabetes care shifted from crisis management to long-term treatment. This history shows how clinical observation, laboratory rigor, and collaboration created a lifesaving therapy. It also clarifies why supply, access, and innovation still matter today.

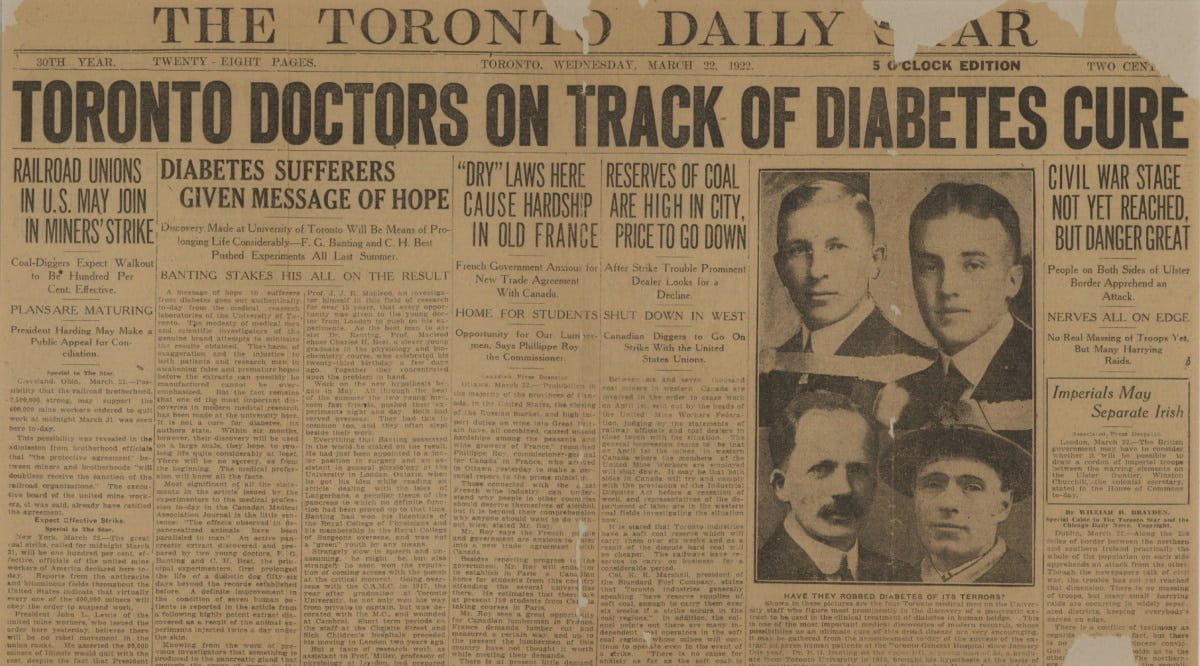

The Discovery of Insulin

Before 1921, severe diabetes usually led to extreme weight loss and early death. Researchers had clues: in 1889, Oskar Minkowski and Joseph von Mering linked the pancreas to diabetes in dogs. In 1910, Edward Sharpey-Schafer proposed a pancreatic substance he called insulin, anticipating the hormone’s role. Building on these ideas, Frederick Banting, a surgeon, developed a plan to isolate pancreatic extracts that might lower blood sugar.

Working at the University of Toronto with medical student Charles Best, Banting tested crude extracts on depancreatized dogs. Their results showed clear glucose reductions. James Collip then refined the extract, improving purity and safety. By late 1921, the team had a potent preparation ready for clinical testing. The group’s work moved rapidly from animal experiments to hospital trials in early 1922.

Diabetes Before Insulin: Treatments and Outcomes

Before insulin, physicians relied on extreme low-calorie diets, fasting, and restricted carbohydrates. These plans sometimes delayed symptoms but caused malnutrition. Children with type 1 diabetes (autoimmune insulin deficiency) rarely survived for long. Families faced daily uncertainty, and clinicians had little to offer beyond careful diet and supportive care.

Researchers used biochemical tests to track sugar in urine, but no therapy corrected the underlying hormone loss. Physicians like Elliott P. Joslin documented survival with strict diets, yet outcomes remained poor. For context on disease patterns and care frameworks, see the Type 1 Diabetes category for structured overviews of diagnosis and management today (Type 1 Diabetes) because modern treatment contrasts sharply with historical practice.

From Lab to Clinic: First Human Use and Early Production

In January 1922, Leonard Thompson, a 14-year-old with severe diabetes, became the first patient to receive purified pancreatic extract at Toronto General Hospital. The initial injection caused limited benefit and reactions, likely from impurities. After Collip’s refinement, a second course produced dramatic clinical improvement and reduced glucose readings. Physicians now had a reliable intervention that reversed key symptoms.

The success prompted a scale-up effort, with pharmaceutical partners helping to standardize extraction and testing. Hospitals saw rapid adoption across North America and Europe. For clinical background on modern basal therapies, review the pharmacology in our overview of long-acting analogs, including glargine, which contextualizes dose profiles and safety considerations (Insulin Glargine Uses), to understand how today’s options evolved from these first extracts.

Credit, Conflict, and Collaboration

Assigning credit proved complicated because many people contributed. Frederick Banting led the initial concept and animal experiments. Charles Best worked closely at the bench; John Macleod provided lab space, guidance, and oversight. James Collip introduced crucial chemical purification that enabled safe human use. In 1923, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine went to Banting and Macleod, and Banting shared his portion with Best; Macleod shared with Collip.

Disagreements over priority, roles, and publication timing fueled debates then and now. For a concise primary source, the Nobel Prize announcement summarizes the committee’s rationale and the award’s context (Nobel Prize 1923). This record helps readers weigh the evidence behind insulin discovery and controversy, clarifying how scientific work often depends on both individual insight and institutional support.

How Insulin Is Made Today: From Extracts to Recombinant DNA

Early preparations came from animal pancreases, primarily bovine and porcine sources. Modern manufacturers use recombinant DNA techniques to program microbes such as Escherichia coli or yeast to produce human insulin. The protein is then purified, folded correctly, and formulated with stabilizers. This approach enables consistent quality and large-scale supply. For a production overview and organ-level context, see our explainer on synthesis and secretion in different tissues (Where Is Insulin Produced) to connect lab methods with physiology.

Manufacturers adjust amino acids, zinc, and excipients to alter onset and duration, creating rapid-acting and long-acting analogs. These controlled modifications support flexible dosing strategies in clinical practice. If you want a clinical bridge from production science to everyday care, our guide to resistance mechanisms and treatment options explains how therapy selection responds to physiologic challenges (Insulin Resistance Treatment), highlighting why formulation differences matter.

Therapy Evolution and Delivery Methods

Insulin delivery began with reusable glass syringes and steel needles, disinfected by boiling. Modern options include disposable syringes, cartridge pens, and automated pumps. Pens simplify dosing and reduce user error, while pumps can deliver basal rates and programmed boluses. Continuous glucose monitoring reshaped feedback loops, further improving control by aligning dosing with data.

Pen devices now pair with rapid-acting analogs for meals and long-acting analogs for basal needs. To see common mealtime options used with pens, review a device example that illustrates dose increment design and portability (Humalog KwikPen). For basal coverage examples with once-daily regimens, a popular pen platform highlights flow rates and storage guidance (Tresiba FlexTouch Pens). For broader change over decades, this historical overview connects Ultralente-era practice to present-day long-acting choices (Evolution Of Insulin Therapy), showing how design choices respond to clinical problems.

Timelines and Milestones: Key Dates and Developments

Insulin’s timeline includes laboratory discovery, scale-up, regulatory pathways, and biotechnology milestones. In 1982, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first recombinant human insulin, marking a shift from animal extracts to bioengineered production. This milestone reshaped supply reliability and purification standards. Readers can confirm this milestone in an FDA historical note about biotechnology’s early approvals (FDA historical note), which captures how regulatory oversight supported safety and quality.

Analog insulins followed, offering faster onsets or flatter basal profiles. Delivery technologies diversified: pens, pumps, and sensor integration improved day-to-day usability. To put these changes in clinical perspective, see our review of modern care pathways and device-enabled options for type 2 diabetes (Innovations In Type 2 Diabetes), which shows how insulin fits into today’s algorithms alongside non-insulin therapies.

Legacy and Access: “Insulin Belongs to the World”

The original Toronto team assigned their patent to the university for a token $1, reflecting a belief that lifesaving medicines should be widely available. That sentiment is often summarized by the phrase insulin belongs to the world. The phrase underscores a public-spirited approach while acknowledging the need for sustainable production and quality controls.

Archival records from the University of Toronto describe licensing arrangements that encouraged manufacturing while limiting profiteering by the inventors. Readers can explore a concise institutional summary of this policy and its public-health rationale via university archives (University of Toronto archives). For affordability context in modern markets, our analysis discusses contributing factors and potential cost mitigations over time (Humalog Insulin Price), offering neutral background for policy discussions.

Recap

Insulin’s story blends observation, careful experiments, and shared credit. The work in Toronto translated a bold hypothesis into effective therapy within months, changing the outlook for people with diabetes. Advances in biotechnology, pharmacology, and delivery continue to refine treatment, improving stability, convenience, and safety.

Readers who want broader context on diet, education, and chronic care can explore our editorial resources. The diabetes hub offers structured guides that situate insulin among other therapies (Diabetes). For clinical education and public awareness timelines, these curated explainers include campaigns and best-practice tools for people at different stages of care (Diabetes Education Week).

Note: Historical summaries simplify complex events. When assessing timelines, compare multiple credible sources and weigh primary documents where available.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice.