Key Takeaways

- Core role: Insulin binding triggers cellular glucose uptake and metabolism.

- Broad distribution: High density in liver, muscle, and adipose tissue.

- Biology matters: Receptor structure and phosphorylation control signaling strength.

- Diabetes impact: Resistance alters downstream pathways, not just hormone levels.

- Practical angle: Lifestyle and therapy choices can influence signaling.

Understanding insulin receptors helps explain how cells sense insulin and regulate energy. When these proteins work well, glucose moves into cells and fuel use stays balanced. When they fail or become less responsive, blood sugar control becomes harder and complications may follow. This overview keeps mechanisms practical and ties them to everyday care.

What Are Insulin Receptors?

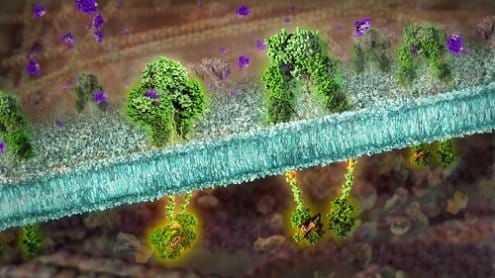

These cell-surface proteins detect circulating insulin and translate its signal into cellular actions. They belong to the receptor tyrosine kinase family and exist as a dimer of two alpha and two beta subunits. The alpha subunits face outward and bind insulin, while the beta subunits span the membrane and contain the catalytic kinase domain. Together, they form a switch that turns on when hormone is present.

After insulin binds, the receptor changes shape and activates its kinase activity. That activation drives phosphorylation events on intracellular proteins, creating docking sites for adaptor molecules. The signal then branches into networks that regulate glucose transport, glycogen synthesis, lipid handling, and gene transcription. In plain terms, the receptor converts a hormone message into metabolic work inside the cell.

Hormone context helps frame the receptor’s job. For a concise contrast between insulin’s storage role and glucagon’s mobilizing role, see Insulin vs. Glucagon for background on counterregulation.

Location and Cell Distribution

Receptors are widely expressed, but their density varies by tissue. Hepatocytes in the liver, skeletal muscle fibers, and adipocytes have high levels because they handle most systemic glucose disposal. Endothelial cells, ovarian theca cells, neurons, and immune cells also express the receptor, supporting diverse roles in vascular tone, reproduction, brain signaling, and inflammation.

Clinically, it helps to ask which cells have insulin receptors when interpreting lab results or responses to therapy. For example, exercise primarily affects skeletal muscle responsiveness. The liver manages fasting glucose output, while adipose tissue influences lipid flux and inflammatory signals. Understanding this distribution clarifies why the same dose can have different effects across organs and why lifestyle changes target specific tissues.

Structure and Activation Mechanism

The receptor is synthesized as a single polypeptide, then cleaved into alpha and beta chains linked by disulfide bonds. The extracellular alpha domains recognize insulin with high specificity. The transmembrane beta chains contain the catalytic kinase that adds phosphate groups to specific tyrosine residues after activation. This arrangement allows sensitive hormone detection at the surface and potent signal amplification inside the cell.

A key structural insight is that this protein functions as an insulin receptor tyrosine kinase. Autophosphorylation on beta subunit tyrosines increases catalytic activity and creates binding sites for insulin receptor substrates (IRS proteins). Downstream, adaptor proteins and enzymes assemble into signaling complexes. The efficiency of these steps depends on receptor abundance, membrane microdomains, and competing kinase or phosphatase activity within the cell.

The Signaling Pathway

Two major branches drive metabolic and growth effects. The PI3K–AKT pathway promotes GLUT4 translocation in muscle and adipose tissue, increases glycogen synthesis, and modulates lipid metabolism. The MAPK/ERK pathway influences gene expression, cell growth, and differentiation. Together, these arms coordinate short-term fuel handling with longer-term cellular programs.

In brief, the insulin signaling pathway starts with receptor activation, IRS phosphorylation, recruitment of PI3K, and generation of PIP3. That lipid second messenger activates AKT, which then affects transporters, enzymes, and transcription factors. For a clinician-level primer, see the insulin signaling network overview, which consolidates mechanisms and experimental data. For practical levers that improve downstream responses, see Improving Insulin Sensitivity for exercise and nutrition strategies.

How Diabetes Alters Signaling

In insulin resistance, multiple checks fail across the cascade. Receptor number may decline modestly, but post-receptor defects dominate. Serine phosphorylation of IRS proteins, lipid intermediates, and inflammatory mediators interfere with signal flow. This explains what happens to insulin receptors in type 2 diabetes at the functional level: even with normal or high insulin, signaling can be blunted and delayed.

In autoimmune deficiency, circulating insulin falls or disappears, so otherwise intact receptors remain under-stimulated. Cells cannot maintain glucose uptake without replacement hormone, and fasting output from the liver rises. Clinicians differentiate these states by history and labs rather than surface expression alone. For a clear contrast, see Insulin Resistance vs Insulin Deficiency for distinguishing features, and Best Diet for Insulin Resistance for nutrition patterns that may support signaling.

Clinical Relevance and Testing

Everyday clinics do not measure receptor content directly. Instead, they estimate insulin action using fasting glucose and insulin (e.g., HOMA-IR), oral glucose tolerance tests, or, in research, the euglycemic clamp. These tests reflect pathway performance more than receptor abundance. Interventions are then tailored to improve whole-system sensitivity and compensate for defects upstream or downstream of the receptor.

Rarely, genetic variants affect insulin receptor structure and function, producing severe insulin resistance syndromes. In typical cases, polygenic risk, adiposity, sleep, and inactivity weigh more than single-gene effects. Treatment focuses on weight management, physical activity, and pharmacotherapy. For medication mechanisms that influence pathway nodes, see Common Diabetes Medications for drug classes and targets. For broader learning, browse Diabetes Articles to place receptor biology within everyday care.

Practical Implications for Therapy and Lifestyle

Resistance can improve with consistent exercise, fiber-rich diets, and sufficient sleep. Muscle contractions bypass parts of the cascade, increasing glucose uptake even when signaling is impaired. Over time, training increases mitochondrial capacity and reduces ectopic lipids that disrupt signaling. Nutrition patterns emphasizing whole foods, adequate protein, and balanced carbohydrates can further support metabolic control.

Pharmacotherapy replaces missing hormone or augments cellular responses. Exogenous insulin binds the receptor and triggers insulin receptor activation similarly to endogenous hormone. Onset and duration vary by formulation, which shapes mealtime and basal strategies. For examples of rapid options used around meals, see Insulin Dosage Chart for timing concepts; compare Humalog Cartridge 100 units/mL for fast-acting use cases and Humulin R 100 units/mL for short-acting contexts, as discussed when aligning therapy to meals. For weight considerations during therapy, see Insulin and Weight Gain for mechanisms and mitigation strategies.

Therapeutic planning should follow established guidance and individual goals. For consensus recommendations on targets and treatment principles, review the ADA Standards of Care, which integrate pharmacologic and lifestyle approaches. Clinicians can adapt these frameworks to patients’ comorbidities and preferences.

Visualizing the Pathway

Sketches and pathway maps can clarify complexity. Start with the receptor at the membrane, then draw IRS proteins, PI3K, and AKT leading to GLUT4 vesicles. Add the parallel MAPK branch for growth signals. Finally, annotate common inhibitors, such as inflammatory kinases, and places where exercise provides alternate routes. A simple figure helps connect interventions to specific pathway steps.

When teaching or learning, pair a pathway sketch with a case. For instance, map how resistance in muscle affects post-meal glucose, then show how a brisk walk improves transporter trafficking. Layer in nutrition and sleep to demonstrate synergistic gains. This approach makes the mechanism memorable and directly actionable in daily routines.

Recap

Receptor biology links hormone levels to cellular outcomes. Structure and phosphorylation control how efficiently cells respond, and context—tissue type, activity, and inflammation—shapes the result. In diabetes, improving sensitivity and matching therapy to physiology can restore balance.

Note: Mechanistic understanding does not replace individualized care. Use it to interpret responses, refine plans, and communicate clearly with patients.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice.