Aging changes the body’s metabolism, cognition, and functional reserve. These shifts can complicate day-to-day glucose control and long-term risk. Many care plans work better when tailored to the realities of late life. Early recognition, simplified regimens, and steady routines help people living with geriatric diabetes maintain independence and safety.

Key Takeaways

- Individualized targets: align goals with function, comorbidities, and preferences.

- Simplify safely: fewer medications and clear routines reduce hypoglycemia risk.

- Screen wisely: focus on symptoms, vision, feet, kidneys, and cognition.

- Food and movement: small, consistent habits help stabilize daily glucose.

- Plan for support: involve caregivers and use reminders and monitoring tools.

Understanding Geriatric Diabetes in Older Adults

Diabetes in older adults often presents differently than in midlife. Aging lowers beta-cell reserve, reduces insulin sensitivity, and changes appetite and muscle mass. Coexisting conditions, polypharmacy, and cognitive changes can further destabilize daily glucose. These factors raise the chance of low blood sugar, falls, and hospitalizations if treatment is not adjusted thoughtfully. For a broader overview of related topics on our site, see Diabetes Articles for context across screening, treatments, and self-care.

Prevalence increases with age, and multimorbidity is common. Older adults may face overlapping concerns such as frailty, chronic kidney disease, or neuropathy that interact with glycemic therapy. Public health data continue to show rising diabetes burden with aging populations; for recent context, review the National Diabetes Statistics Report, which summarizes prevalence and complications in the U.S.

Age, Physiology, and the Course of Disease

Age-related changes in body composition include reduced lean muscle and increased visceral fat. These shifts decrease insulin sensitivity, leading to higher post-meal glucose excursions. Kidney function often declines with age, extending the effect of certain medications and heightening hypoglycemia risk. Neuropathy, vision changes, and arthritis can also interfere with injections, fingersticks, and safe exercise.

Clinical presentations may be subtle. Instead of classic thirst and urination, some seniors show fatigue, confusion, or weight loss. Dehydration, infections, and medication interactions further complicate the picture. Recognizing these patterns helps clinicians and families adjust monitoring routines and therapy intensity to keep daily life steady.

Recognizing Symptoms and Acting Early

Early detection matters because delayed diagnosis can lead to avoidable complications. Practical cues include unexpected weight loss, excessive fatigue, recurrent urinary tract infections, and slow-healing wounds. Women may report vaginal itching or new infections, while men might notice erectile difficulties. Hydration status and appetite changes offer additional clues during routine check-ins.

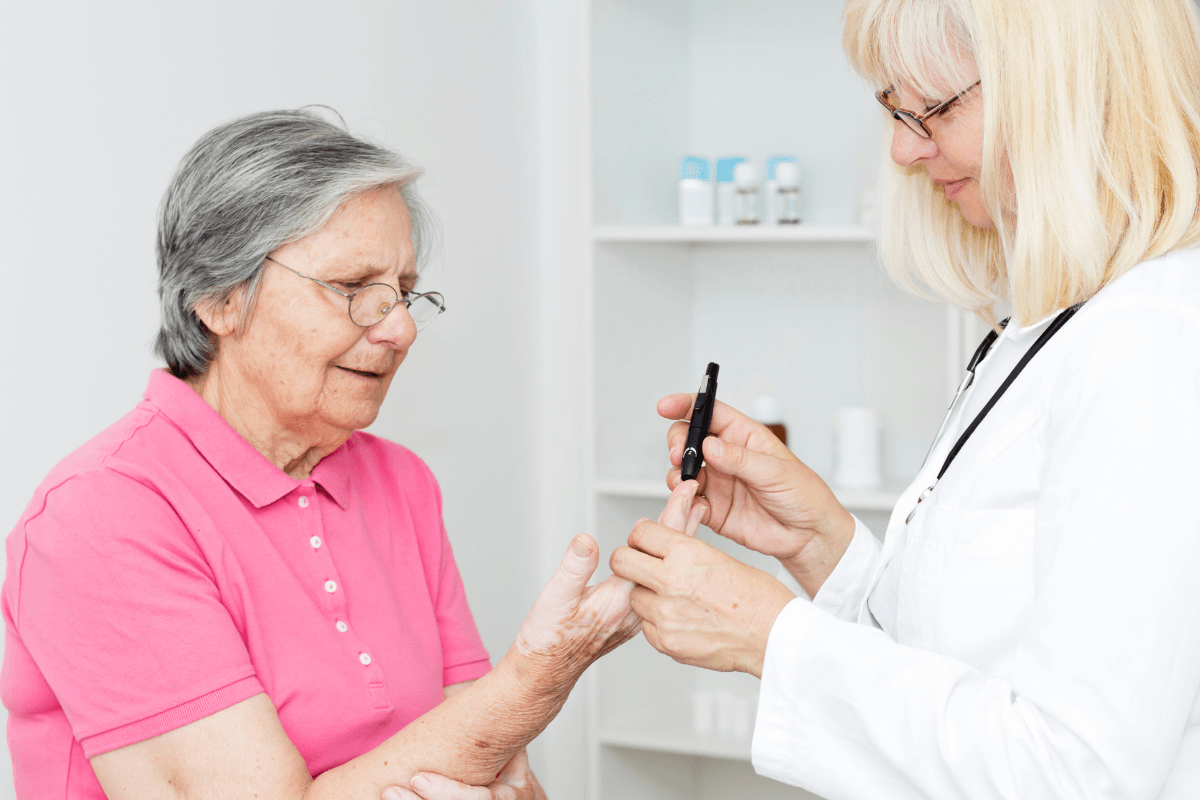

People often ask what are the first signs of diabetes in seniors, and the list usually includes increased urination, thirst, blurry vision, and persistent fatigue. When these symptoms appear, timely lab testing—fasting glucose, A1c, or an oral glucose tolerance test—can clarify the picture. For a detailed review of hallmark features by type, see Type 2 Diabetes Signs to compare common symptoms and next steps. For home testing basics, see How To Check Sugar Level At Home to set up simple routines and verify readings.

Screening and Targets: Updated Guidance

Glycemic targets in later life should reflect function, comorbidities, and hypoglycemia vulnerability. Healthier, independent adults may maintain moderately tight control, while those with complex illness or limited life expectancy may benefit from relaxed goals to avoid lows. Blood pressure, lipids, kidney function, and vaccinations remain important in comprehensive care.

Clinicians often consider ada a1c guidelines for older adults when individualizing goals and medications. The latest recommendations emphasize avoiding hypoglycemia, simplifying regimens, and reassessing targets as health status changes. For detailed evidence and age-specific nuances, consult the ADA Standards of Care, including the older adults chapter. Medication selection should align with kidney function, fall risk, and cognitive status; for mechanism overviews, see Common Diabetes Medications for class-by-class pros and cons.

Medication Choices, Simplification, and Safety

Complex regimens increase confusion and dosing errors. Where possible, clinicians may favor once-daily dosing, combination pills, or streamlined injection schedules. Agents with lower hypoglycemia risk are often prioritized, especially for those living alone or with fluctuating appetite. Deintensification can be appropriate when the treatment burden outweighs benefits.

Side effect profiles matter. For example, gastrointestinal tolerance, dizziness, and dehydration can cause falls or weight loss in frail adults. Regular medication reviews help identify drug–drug interactions and opportunities to reduce complexity. To understand specific risks, see Jentadueto Side Effects for a representative DPP-4/metformin combination discussion and potential precautions.

Practical Steps to Streamline Therapy

Start by listing current prescriptions, over-the-counter drugs, and supplements, then discuss the list with a clinician or pharmacist. Consider prefilled pens or blister packs to reduce handling demands. Align dosing with daily anchors such as breakfast or bedtime. Involve caregivers where needed and use pill organizers or phone reminders. Finally, schedule periodic reviews to confirm that regimen complexity still matches health status and living situation.

Nutrition and Activity for Stability

Regular meal timing, adequate protein, and fiber-rich foods help stabilize daily glucose. Small, frequent meals may suit those with poor appetite or early satiety. Hydration supports kidney function and reduces dizziness. Gentle strength training and balance work can preserve muscle, improve insulin sensitivity, and lower fall risk when supervised appropriately.

Many families ask, “how can i prevent diabetes naturally” when supporting older relatives. Focus on pragmatic changes: vegetables at most meals, lean proteins, whole grains if tolerated, and limited refined sugars. Short, frequent walks and light resistance bands can be safer than sporadic intense exercise. If cooking is hard, consider ready-to-eat options that meet protein and fiber goals without excess sodium.

Tip: Pair a 10–15 minute walk with the day’s largest meal to blunt post-meal glucose rises while monitoring energy and balance.

Managing Complications and Multimorbidity

Complications may present subtly in later life. Routine foot checks, annual retinal exams, and urine albumin tests can catch early changes before they affect function. Cardiovascular risk reduction remains central, including blood pressure control, statins when indicated, and smoking cessation support. Balance and vision assessments help prevent falls and fractures.

Care plans should anticipate diabetes elderly complications and build around prevention. For eye health specifics and protective steps, see Diabetic Eye Disease to understand screening intervals and warning signs. For skeletal risks, review Bone Problems Associated With Diabetes to align bone health strategies with glucose care. Cardiometabolic overlap is common; for broader strategies, see Manage Heart Health With Diabetes to integrate activity, diet, and medication choices.

Blood Sugar Variability and Hypoglycemia

Fluctuations can stem from irregular meals, missed doses, dehydration, illness, or changing kidney function. Appetite and activity levels also vary day to day, especially during acute illness. These swings may cause dizziness, confusion, or falls. Educating caregivers to recognize shakiness, sweating, or sudden mood changes can prompt timely glucose checks.

Clinicians often address erratic blood sugar levels in elderly patients by simplifying regimens and adjusting targets. Glucose logs that capture meals, activity, and symptoms can reveal patterns more clearly than numbers alone. When possible, avoid medications with high hypoglycemia risk for those with prior severe lows. For prevention and treatment principles, see the NIDDK hypoglycemia guidance, which summarizes symptoms and stepwise responses.

Prevention Across the Lifespan

Even modest lifestyle adjustments can delay progression from prediabetes, especially when habits are consistent. Focus on weight maintenance, sleep quality, and daily movement appropriate to fitness and mobility. Family support helps reinforce routines and reduces isolation, which can undermine self-care. Screening for hearing, vision, and depression also supports adherence.

Practical steps explain how to avoid diabetes in old age, including everyday choices like limiting sugar-sweetened beverages and keeping protein at each meal. Some readers may also encounter the term Type 4 in discussions of age-related insulin resistance; for context, see What Is Type 4 Diabetes to learn how researchers use the label and its limitations.

Care Planning, Support, and Tools

Shared decision-making aligns treatment with the person’s goals, living situation, and support network. Consider who can assist with shopping, cooking, medications, and appointments. Memory prompts—lists on the fridge, phone alarms, or calendar notes—are low-cost aids that improve consistency. When technology is acceptable, continuous or intermittent glucose monitoring can reveal trends and reduce fingersticks.

Education should be bite-sized and reinforced over time. Provide written summaries, demonstrate devices, and confirm understanding. Encourage regular eye, foot, dental, and kidney checks. When reviewing therapy choices, discuss both benefits and trade-offs explicitly. For ongoing learning across topics, our Diabetes Articles section curates practical guides and condition primers suitable for caregivers and older adults.

Recap

Older adults benefit from individualized targets, streamlined therapy, and steady daily routines. Focus on safety, symptom awareness, and manageable lifestyle shifts. Involve caregivers and revisit plans as health status changes. A practical, patient-centered approach supports function, independence, and quality of life.

Note: External clinical resources cited above are provided for general education and may be updated periodically by the issuing organizations.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice.