Key Takeaways

This guide examines Vitamin E and Diabetes with balanced evidence, practical context, and safety notes for everyday care.

- Evidence at a glance: modest effects on biomarkers; mixed clinical outcomes.

- Primary role: antioxidant support; not a replacement for medications or diet.

- Safety first: mind dose limits, bleeding risk, and drug interactions.

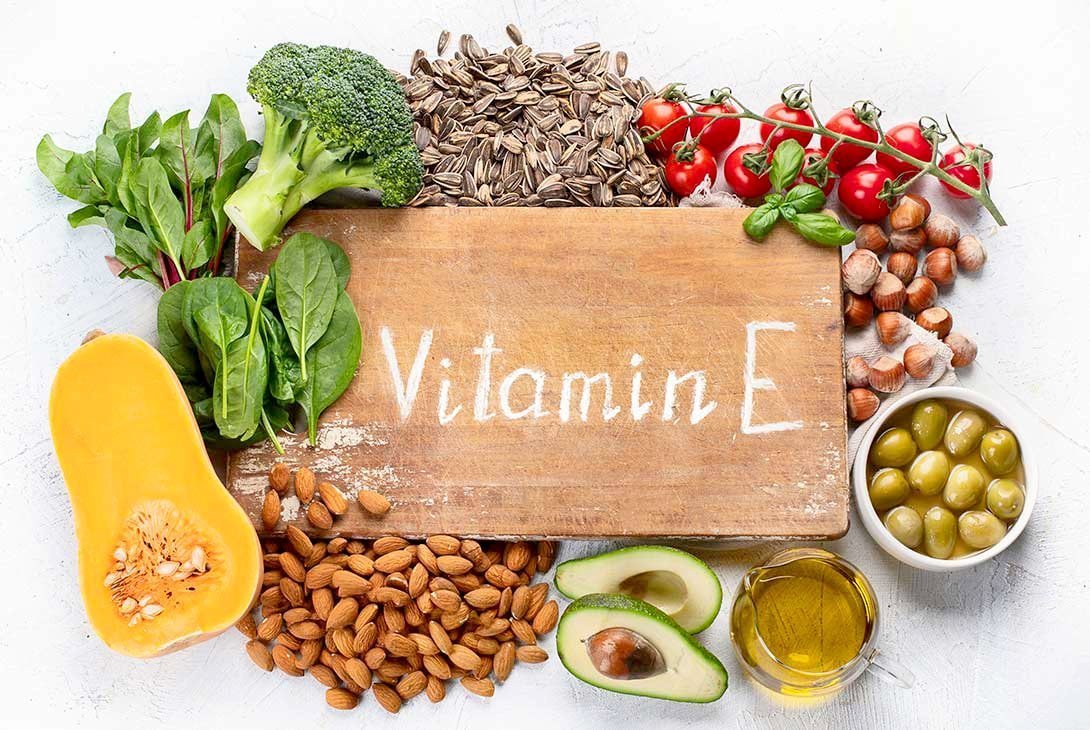

- Food-first approach: prioritize nuts, seeds, and oils before supplements.

Vitamin E and Diabetes: What the Evidence Shows

Vitamin E refers to a family of fat-soluble antioxidants, including tocopherols and tocotrienols. In diabetes, oxidative stress and chronic inflammation can drive vascular and nerve damage. Studies show vitamin E can reduce oxidative markers and improve select lipid parameters. However, its effects on A1C, fasting glucose, and hard outcomes remain inconsistent across trials.

Current guidelines emphasize cautious use. Major organizations have not endorsed routine antioxidant supplementation to improve glycemia in diabetes. For context on broader nutrition guidance, see the ADA Standards of Care, which note limited benefits of antioxidant supplements for glucose control. For dosing limits and interaction details, consult the NIH’s official fact sheet.

Antioxidant strategies should complement, not replace, foundation therapies. For antioxidant context beyond vitamin E, compare approaches in our Vitamin C and Diabetes guide, which outlines another common micronutrient used for oxidative stress.

Mechanisms: Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Lipids

Hyperglycemia increases reactive oxygen species, damaging cell membranes and vascular endothelium. Vitamin E integrates into lipid layers and interrupts lipid peroxidation. This antioxidant action may help limit oxidative injury in nerves, retina, kidneys, and vessels. Some studies report small improvements in inflammatory markers and endothelial function when vitamin E status improves.

Mechanistically, it may also influence insulin signaling pathways and adipocyte biology. Trials assessing Best Diet For Insulin Resistance show diet remains the primary lever for insulin action; supplementation is secondary. In small cohorts, vitamin E has been linked to improved vitamin e insulin sensitivity measures, but effects are not uniform. Lipid changes, such as reduced LDL oxidation and modest triglyceride shifts, are reported in select groups.

Evidence in Type 2 Diabetes

Research in type 2 diabetes spans glycemic markers, lipid profiles, and vascular endpoints. Some randomized trials show small reductions in oxidative biomarkers and LDL oxidation, with occasional improvements in triglycerides. Effects on A1C and fasting glucose are mixed and often clinically modest. Lifestyle, weight, and medication regimen usually explain more variance than supplementation.

Diet quality and whole-food patterns consistently drive outcomes. For practical meal planning, our Role of Diet in Diabetes Management overview links core nutrition choices to glycemic stability. Specific carbohydrate quality also matters; see Brown Rice and Diabetes for evidence on whole grains that support A1C. While some studies report benefits in vitamin e type 2 diabetes, routine supplementation for glucose control alone is not established.

Evidence in Type 1 Diabetes

Trials in type 1 diabetes are fewer and generally smaller. Findings suggest reductions in oxidative stress markers, but consistent A1C improvement is not demonstrated. Any potential benefits appear secondary to standard insulin therapy, glycemic monitoring, and cardiometabolic risk reduction. Vitamin E may support redox balance, yet hard outcomes remain inconclusive.

Complication prevention still relies on time-in-range glucose, lipids, and blood pressure control. For micronutrient comparisons across endocrine conditions, explore Vitamin D and Diabetes, which outlines bone, immune, and metabolic links. Given mixed data in vitamin e type 1 diabetes, decisions should weigh individual diet, labs, and comorbidities.

Safety, Interactions, and Dosing Considerations

Vitamin E safety depends on dose, form, and clinical context. High intakes may increase bleeding risk, particularly with anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs. The tolerable upper intake level (UL) for adults is 1,000 mg/day of alpha-tocopherol (doses on labels may list IU). The NIH health professional fact sheet details conversions and cautions. Adverse effects can include GI discomfort and, at very high doses, hemorrhagic risk.

In practice, discuss vitamin e dosage for diabetics in the context of diet quality, current lab values, and medications. Avoid megadoses unless a clinician identifies a deficiency or specific indication. If you take anticoagulants, antiplatelets, or high-dose omega-3s, review bleeding risk. Consider periodic medication reconciliation when starting or stopping supplements to manage potential interactions.

Drug and Nutrient Interactions

Metformin remains foundational for insulin resistance and cardiometabolic risk. For background on its broader role, see Metformin in Prediabetes, which explains B12 considerations and preventive use. No strong evidence confirms a clinically significant vitamin e and metformin interaction, but both nutrient status and polypharmacy warrant review.

Medication examples help frame risk discussions. If you use Glumetza, coordinate any new supplements to monitor GI tolerance and labs. For dyslipidemia, fibrates can target triglycerides; see Fenofibrate for an example of a therapy often considered when triglycerides are elevated. Blood pressure control intersects with vascular risk; ACE inhibitors such as Altace are part of many care plans. Always align supplement choices with the full medication list.

Food Sources, Forms, and Choosing Supplements

A food-first approach provides vitamin E alongside fiber, minerals, and phytochemicals. Emphasize nuts, seeds, and plant oils, where mixed tocopherols naturally occur. These foods fit well within Mediterranean-style patterns that support lipid control and glycemic stability. For readers seeking natural sources of vitamin e for diabetics, the table below summarizes common options and typical amounts.

| Food | Serving | Vitamin E (mg) |

|---|---|---|

| Almonds | 28 g (1 oz) | ~7.3 |

| Sunflower seeds | 28 g (1 oz) | ~7.4 |

| Hazelnuts | 28 g (1 oz) | ~4.3 |

| Wheat germ oil | 1 tbsp | ~20 |

| Avocado | 1/2 medium | ~1.3 |

| Spinach (cooked) | 1/2 cup | ~1.9 |

Supplement forms vary: natural d-alpha-tocopherol and synthetic dl-alpha-tocopherol differ in potency, and mixed tocopherols or tocotrienols add complexity. Evidence does not establish one universally superior form for glycemic control. If supplements are considered, choose third-party tested products and align dosing with overall diet. For broader supplement reading, browse our Vitamins & Supplements category for additional micronutrient guides.

Microvascular Complications and Vision

Oxidative stress contributes to microvascular injury in eyes, kidneys, and nerves. Research exploring vitamin e diabetic retinopathy signals potential antioxidant benefits, but results are heterogeneous. No consensus supports vitamin E alone to prevent or treat retinal disease. Vision protection still depends on glucose control, blood pressure, and routine ophthalmic screening. For timely prevention messages and screening reminders, see Diabetic Eye Disease Month.

Nerve health, wound repair, and kidney function involve complex pathways beyond redox balance. Balanced diets rich in unsaturated fats, green vegetables, and lean proteins support systemic health. For lipid-focused meal ideas that can help triglyceride management, our Best Fish Choices guide discusses omega-3 sources and simple preparation tips. When comparing antioxidants across nutrients, Vitamin C and Diabetes offers additional context for everyday choices.

Recap

Vitamin E offers antioxidant support that may modestly affect oxidative markers, lipids, and vascular biology. Evidence for direct glycemic benefits remains inconsistent, and supplement use should not replace medications, dietary patterns, or activity. Individualize decisions using labs, comorbidities, and the full medication list. For wider reading across topics, visit our Diabetes Articles hub for diet, medication, and complication overviews.

Note: External guidance on safety and dosing is available from the NIH and professional societies. See the NIH’s health professional fact sheet for upper limits and interaction details.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice.