Diabetes affects more than blood sugar; it can also drive bone problems through changes in hormones, nerves, and blood vessels. Understanding the mechanisms helps you spot risks early and protect long-term skeletal health.

Key Takeaways

- Higher fracture risk: diabetes alters bone quality and fall risk.

- Silent changes: bone density may look normal yet remain fragile.

- Medications matter: some agents can influence bone turnover.

- Screen, then act: DEXA, labs, and foot checks guide care.

- Small habits add up: protein, vitamin D, and strength training help.

How Diabetes Drives Bone Problems

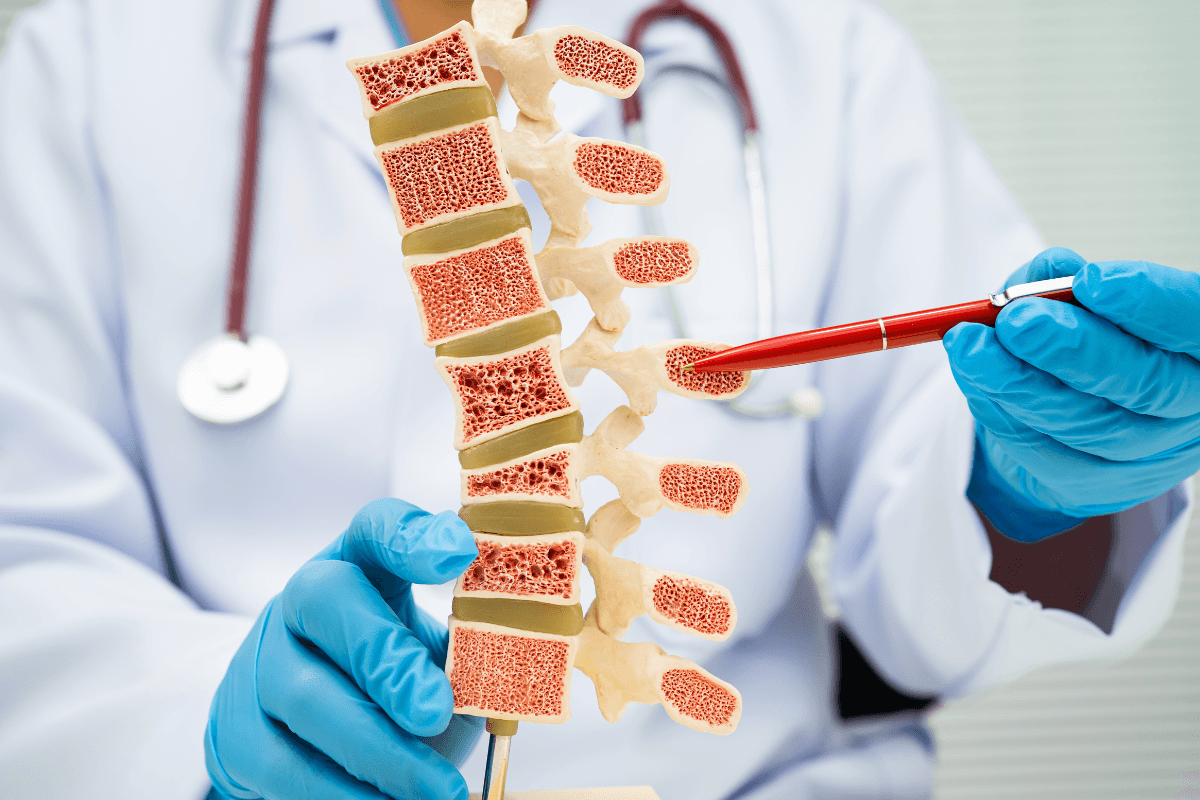

Diabetes disrupts bone remodeling by affecting osteoblasts (bone builders) and osteoclasts (bone resorbers). Chronic hyperglycemia leads to advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) that stiffen collagen, reducing bone toughness even when mineral density appears normal. Autonomic and peripheral neuropathy can also impair balance and protective reflexes, increasing falls and fracture severity.

Microvascular disease reduces perfusion to bone and marrow, potentially slowing repair after minor injuries. Inflammatory signaling tied to insulin resistance can tip remodeling toward resorption. Together, these pathways explain why fractures sometimes occur from low-energy events and why healing may take longer in people with diabetes.

Osteoporosis Risk and Fracture Patterns

Type 1 diabetes is strongly associated with lower bone mass and higher hip and vertebral fractures. Type 2 diabetes often shows normal or higher bone mineral density, yet microarchitecture may be compromised. That paradox partly reflects cortical porosity and material property changes. Hip, vertebral, and proximal humerus fractures are the most clinically important patterns due to morbidity.

Guidelines increasingly recommend adjusting fracture risk tools when assessing people with diabetes. When counseling patients, highlight fall mechanics, home hazards, and neuropathy-related instability. For a focused discussion on diabetes-specific bone risks, see Osteoporosis and Diabetes for nuances specific to Type 1 and Type 2.

In this section, we reference NIAMS osteoporosis overview to ground definitions and core concepts that underlie fracture prevention strategies.

Specific terms: osteoporosis affects millions globally and drives fragility fractures. Here, you will see the term osteoporosis once to anchor the clinical link between diabetes and bone strength.

Recognizing Warning Signs and Diagnostics

Fractures after low-impact events, height loss, or chronic back pain may point to underlying bone disease symptoms. Recurrent sprains, slow healing after minor trauma, and foot deformities can also signal impaired mechanics. In diabetes, neuropathy can mask pain, so subtle changes like reduced grip strength or cautious gait deserve attention.

Diagnostic workups typically include history, medication review, and nutritional assessment. Labs may evaluate calcium, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone, renal function, and thyroid status. In people with longstanding diabetes, clinicians may add markers of bone turnover and screen for secondary contributors like hypogonadism. For context on fracture pathways, see Diabetes and Bone Fractures for a plain-language overview of mechanisms.

Medicines, Glucose Levels, and Bone Biology

Some glucose-lowering medications and comorbid therapies may influence remodeling. Thiazolidinediones can shift mesenchymal stem cells toward adipocytes, potentially reducing bone formation. Steroids for inflammatory disease accelerate resorption, especially with prolonged use. Clinicians weigh glucose control with skeletal safety on a case-by-case basis.

People should report new aches or gait changes promptly, especially if they emerge after medication changes, because these can overlap with metabolic bone disease symptoms. For context on insulin sensitizers, see Metformin vs Avandia to understand class differences relevant to bone risk. For SGLT2-related safety considerations, see Jardiance Side Effects for class effects and monitoring tips.

Regulators also discuss bone signaling in drug labels. The pioglitazone label notes fracture risk signals observed in some populations; clinicians interpret these alongside current trial data and individual risk profiles.

Screening: DEXA, Labs, and Foot-Bone Health

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) remains the standard for bone density, but in diabetes it may underestimate fragility. Trabecular bone score (TBS) and adjunct imaging can refine risk estimates when available. Clinical fall risk assessments, vision checks, and neuropathy exams complement imaging to build a clearer picture of skeletal vulnerability.

People with diabetes benefit from regular foot evaluations because Charcot neuroarthropathy can silently deform joints. Consider referring to podiatry or orthopedics when shape changes or swelling occur. For targeted steps that reduce lower-limb complications, see Foot Screening for Diabetes for interval timing and red flags. For bone health screening thresholds, clinicians often consult the USPSTF screening guidance when deciding on DEXA initiation and intervals.

Beyond imaging, clinicians educate people about subtle symptoms of bone disorders that might otherwise be dismissed as routine aches. Clear timelines for reporting new pain, deformity, or mobility decline enable earlier intervention and safer recovery planning.

Prevention: Nutrition, Activity, and Falls

Protein intake, calcium, and vitamin D support remodeling; most adults aim for 1.0–1.2 g/kg/day of protein, with dietitian input for kidney disease. Resistance and impact training improve bone strength and balance; start with supervised, progressive plans to reduce falls. Vision, footwear, and home hazard checks (lighting, cords, rugs) meaningfully lower fracture risk.

Glucose management still matters. Wide glycemic swings can impair attention and balance, while chronic hyperglycemia undermines bone material quality. Alcohol moderation, smoking cessation, and adequate sleep support overall musculoskeletal health. For broader diabetes education that ties into prevention, browse the Diabetes Articles library to connect related self-care topics.

Tip: Add 800–1,000 IU/day of vitamin D only after checking baseline levels and considering kidney function; more is not always better.

Treatment Options and Care Pathways

Care plans combine lifestyle, fall prevention, and pharmacotherapy when indicated. Antiresorptives and anabolics may reduce fracture risk; selection depends on sex, menopause status, renal function, and prior fractures. Clinicians may sequence medications to maximize early gains in high-risk patients, then consolidate with maintenance therapy.

Alongside fracture care, address comorbid conditions and polypharmacy. Therapy choices, infusion schedules, and dental precautions deserve individualized discussion. Health teams also ensure calcium and vitamin D sufficiency and monitor adherence. When discussing options, the phrase bone disease treatment captures these multi-pronged decisions made by clinicians in shared decision-making.

For high-level safety and interaction reviews of diabetes therapies you may be taking concurrently, see the Invokamet page for drug information context, and the Types of Diabetes guide to understand how diagnosis influences risk and therapy.

Special Considerations: CKD, Steroids, and Adolescents

Chronic kidney disease alters mineral metabolism and secondary hyperparathyroidism, amplifying fracture risk. Phosphate retention and low calcitriol complicate calcium balance and turnover. Coordinated care with nephrology supports safe vitamin D analog use and phosphate management. For background on kidney complications and protective strategies, see National Kidney Month for risk factors and practical actions.

Glucocorticoids quickly accelerate bone loss; tapering when possible and adding antiresorptive measures may help. Adolescents with Type 1 diabetes may accrue less peak bone mass, making early activity and nutrition especially important. When new back pain, kyphosis, or early fragility fractures appear, these may reflect symptoms of osteoporosis and warrant formal evaluation.

Emerging research explores oncology-bone-metabolism intersections. For an accessible summary, see Osteosarcoma and Metformin for a research overview that illustrates how metabolic pathways may influence bone tissue behavior.

Connected Topics and Further Learning

Bone health intersects with cardiovascular risk, vision, neuropathy, and foot care. A comprehensive approach aligns glycemic targets, blood pressure control, and lipid therapy with musculoskeletal goals. Patients benefit from clear rehabilitation plans after fractures to restore function and confidence. For a deep dive into fracture mechanisms, balance training, and protective footwear, explore Diabetes and Bone Fractures for practical illustrations and examples.

Medication safety education should be ongoing. Pharmacist consultations often surface interactions or missed opportunities for supplementation. For an organized starting point, review Osteoporosis and Diabetes and then browse cross-linked topics in the Diabetes Articles section to build a personalized reading plan.

Standards groups periodically update recommendations relevant to fracture prevention. See the ADA Standards 2025 for inclusive screening and geriatric considerations that often overlap with bone health.

Recap

Diabetes can quietly weaken bone quality and raise fracture risk through changes in remodeling, neuropathy, and vascular health. Risk does not always correlate with density, so clinicians may layer DEXA with TBS, labs, and fall risk assessments. Thoughtful medication choices and steady glucose control protect both balance and material properties.

Actionable steps include resistance training, adequate protein, calcium, and vitamin D, plus routine foot checks and home fall-proofing. When imaging, labs, or clinical history point to fragility, pharmacotherapy may reduce future fractures. Keep medication reviews current, and escalate care whenever falls, pain, or functional losses appear.

Note: If you use multiple agents for diabetes, review bone considerations during routine visits to align metabolic and musculoskeletal goals.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice.