Key Takeaways

- GI basics: Foods are ranked by how fast they raise blood sugar.

- Context matters: Portion size, fiber, and fat change your response.

- Charts guide choices, but individual testing is still important.

- Glycemic load links GI to serving size for real-world eating.

Used well, the glycemic index helps you plan meals that support steady glucose while fitting your diabetes care plan.

How the Glycemic Index Works

The glycemic index classifies carbohydrate foods by the speed and magnitude of their glucose impact. Researchers feed a standard carbohydrate portion, then compare blood glucose areas under the curve to a reference food. Results fall into low, medium, or high bands. This system summarizes carbohydrate quality, not quantity, so it complements your carbohydrate counting and meal planning.

GI is not the only factor. Food structure, ripeness, processing, and cooking methods can shift responses. Adding protein, fat, or viscous fiber slows digestion and blunts spikes. As background for using GI in diabetes nutrition, see the ADA guidance on GI and meal planning for an evidence-based overview from the American Diabetes Association. If you use rapid-acting insulin with meals, timing also matters; for illustration of fast-acting options, see Apidra SoloStar Pen discussed in our insulin guide.

Why GI Matters in Diabetes Care

People with diabetes often benefit from understanding the Common Diabetes Medications they use and how food choices influence daily control. The glycemic index of foods provides a practical way to compare carb quality across breads, cereals, fruits, and snacks. Lower-GI choices may reduce post-meal excursions, which can support overall time-in-range alongside your prescribed regimen.

GI is especially helpful when selecting staples you eat often. Small swaps add up across the week. For example, choose dense grains, less ripe fruit, and legumes more often. You can also pair carbohydrates with protein-rich foods like tofu or dairy. For plant-based ideas rich in fiber and protein, see our overview of Beans and Diabetes for how legumes help steady absorption.

Reading a Glycemic Index Chart and Food Labels

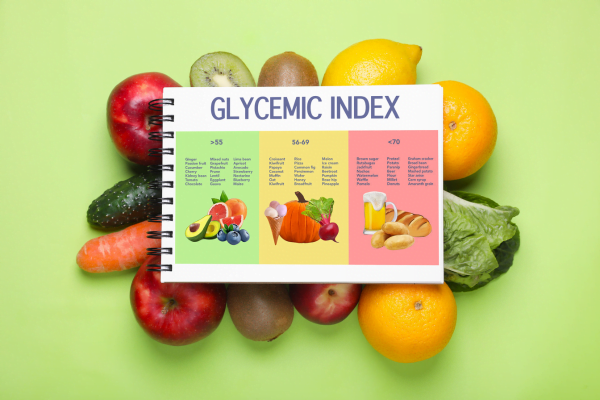

A good glycemic index chart organizes foods by low (≤55), medium (56–69), and high (≥70) ranges, using glucose as the reference. It helps you scan categories and plan substitutions before shopping. For a given category, pick lower-ranked items most of the time, and reserve higher-ranked foods for smaller servings or special occasions.

Food labels do not show GI directly. Still, you can infer pace from fiber, whole-grain content, and degree of processing. Words like “instant,” “flaky,” or “puffed” often indicate faster digestion. When evaluating grains, compare options with a trusted table and your meter or CGM readings. For grain-specific guidance and cooking effects, our article on Brown Rice and Diabetes explains how structure and fiber change post-meal responses.

Glycemic Load, Portions, and Meal Composition

Glycemic load connects food quality with serving size. A moderate portion of a moderate-GI food can produce a low glycemic load, while a large serving of a low-GI food can still raise glucose significantly. This concept helps you balance realistic portions with your carbohydrate targets and medication plan. Harvard’s overview offers a plain-language explanation of GL with examples from Harvard Health Publishing.

Composition matters. Add viscous fiber (oats, barley, beans), lean protein, or healthy fats to slow gastric emptying and flatten the curve. Pair pasta with legumes or fish, or use a smaller portion and bulk the plate with vegetables. For practical plate-building, see Pasta for Diabetics for portion ideas, and consider a specialized supplement like Glucerna when you need a controlled-carb meal replacement as part of a plan you set with your clinician.

How the Glycemic Index Fits Day to Day

Think of GI as a compass, not a rulebook. Start by identifying your high-impact meals: breakfast cereals, breads, rice bowls, and snacks. Choose lower-GI options within the same category to change glucose patterns without overhauling your diet. Keep familiar foods you enjoy, and adjust portions and pairings to suit your targets.

Track your response. Use your meter or CGM to check pre-meal and 1–2 hours post-meal regularly when trialing changes. Compare meals of similar carbohydrate amounts to see how food form or preparation alters your curve. If you use combination therapy or incretin-based agents, that may further smooth post-meal spikes; for context on an incretin option, see Mounjaro KwikPen discussed in our medication section.

Rice and Grains: Choosing Better Staples

Rice is a staple for many households, but varieties and preparation differ. The glycemic index of rice varies with grain length, amylose content, and cooking time. In general, firmer, less processed grains digest more slowly. Cooling cooked rice and reheating can increase resistant starch, which may blunt spikes for some people. As always, check your own readings to confirm effects.

Among everyday choices, long-grain types like basmati tend to be slower than short-grain sticky rice. Parboiled rice often outperforms quick-cook versions. Whole grains such as barley, bulgur, and steel-cut oats are good alternatives for bowls or sides. Pair rice with protein and vegetables to shift the meal’s overall impact. For a deeper dive into variety-specific comparisons, our feature on Tofu for Diabetics includes meal ideas that combine grains and protein effectively.

When assessing options for your pantry, compare the glycemic index of rice with other grains you already use. Then adjust portions while keeping your carbohydrate targets and medications in view. If you are exploring whole-grain breads, fiber-rich wheat options can be more predictable than soft, refined loaves, especially when paired with protein spreads.

Sugar, Sweets, and Smart Swaps

Table sugar and syrups can produce rapid glucose rises, especially in liquid form. The glycemic index of sugar is only part of the story; serving size and context matter. If you include dessert, pair a small portion with a protein-rich meal and consider timing around activity. Fruit-based desserts with skin and pulp often digest more slowly than ultra-refined pastries.

Liquid carbohydrates act fast. Fruit juice can cause marked spikes; monitor closely if you include it. For more details on beverage effects, see Orange Juice and Diabetes for strategies to minimize swings. Conversely, for treating symptomatic lows under your care plan, fast glucose can be appropriate; see Dextrose for examples used in hypoglycemia treatment protocols you develop with your clinician.

Tools, Testing, and Reliable Resources

Digital tools can help you translate GI into daily choices. A simple glycemic index calculator may estimate a food’s impact when you know its GI value and serving size, but it never replaces your meter or CGM. For verified values, consult an authoritative database such as the University of Sydney’s searchable tables at the GI Foundation. Compare entries across similar foods before deciding on routine swaps.

Individual responses vary by microbiome, medications, and cooking habits. When you test new meals, change one factor at a time and record pre- and post-meal readings on at least two occasions. If you need more nutrition content organized by topic, browse our Diabetes collection for practical food guides, including Tomatoes and Diabetes and Strawberries and Diabetes, which discuss fruit choices and meal pairing.

Recap

GI is a useful lens for comparing carbohydrate foods, but it lives alongside portion size, meal composition, and your prescribed therapy. Start with common staples, choose slower-digesting options, pair with protein and fiber, and verify with your own readings. Use curated charts and reputable databases to guide choices, and adjust based on your glucose patterns and care goals.

Tip: When trying a new staple, test it twice with similar portions to confirm its real effect on your glucose curve.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice.