Ceramides and diabetes share meaningful links in current metabolic research. These lipids sit at the crossroads of cell signaling, inflammation, and energy use. Elevated levels can correlate with insulin resistance and cardiometabolic risk. This guide translates biochemical concepts into practical steps you can use alongside medical care.

Key Takeaways

- Ceramide basics: structural lipids that influence insulin signaling.

- Higher levels may track with insulin resistance and risk.

- Food pattern, movement, sleep, and weight management help.

- Supplements and newer therapies remain adjuncts, not cures.

- Discuss testing and changes with your healthcare professional.

What Are Ceramides? Definition and Role

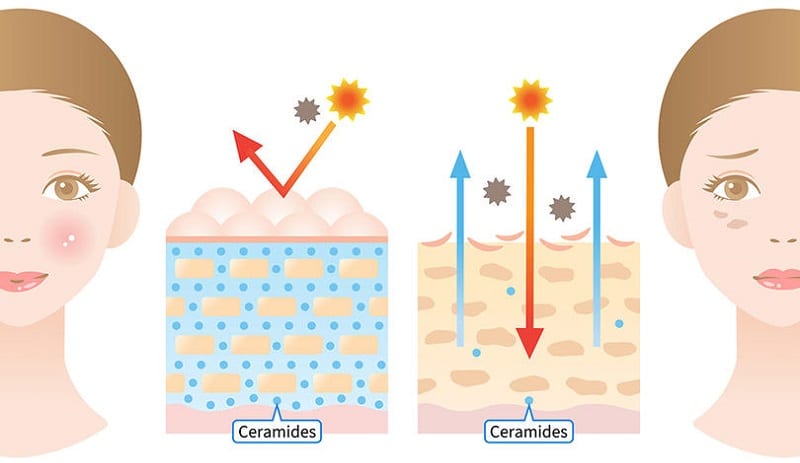

Ceramides are waxy, fat-like molecules found in cell membranes. They belong to the broader sphingolipid family and act as bioactive messengers. In the skin, they help lock in moisture and maintain a barrier. Inside organs like liver and muscle, they influence metabolic signaling and stress responses.

In simple terms, ceramide definition refers to a lipid composed of a sphingoid base linked to a fatty acid. Clinically, researchers track ceramide species because certain patterns may align with metabolic risk. In plain language, higher levels can signal that cells are struggling to respond to insulin effectively.

Ceramide Structure and Function in Metabolic Health

Biochemically, ceramides are built from a long-chain base (often sphingosine) attached to a fatty acid. This backbone shapes membrane properties and cell signaling. Different chain lengths and saturation levels may have distinct biological effects. You might see this discussed as ceramide composition or a sphingolipid profile in laboratory reports.

Functionally, ceramide structure and function tie into stress-activated pathways. Ceramides can influence how insulin receptors communicate with downstream enzymes. In muscles, they may interfere with glucose uptake when elevated. In the liver, they can shift fat handling and inflammatory signals. These shifts help explain why metabolic context, not single nutrients, matters most.

Ceramides and Diabetes: How Lipids Disrupt Insulin Signaling

Insulin resistance (reduced response to insulin’s signal) often precedes type 2 diabetes. Ceramides may impair key steps in insulin signaling pathways, particularly those controlling glucose uptake. Over time, these disruptions can contribute to hyperglycemia and cardiometabolic strain. The overall picture combines genetics, diet, activity, sleep, and body composition.

For a concise clinical background on insulin resistance and related risks, see the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases insulin resistance overview. This provides neutral context on mechanisms and health implications. Emerging research also explores how tissue-specific ceramides track with outcomes, yet standardized thresholds are still evolving.

Dietary Sources and How to Reduce Ceramides

Diet shapes lipid metabolism through energy balance, fatty acid mix, and fiber. Whole-food, plant-forward patterns support healthier lipid handling. Practical steps include more vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds. Limiting ultra-processed foods and excess saturated fat supports metabolic signals.

People often ask about foods that reduce ceramides. Patterns rich in unsaturated fats (olive oil, nuts, fatty fish), high fiber, and moderate carbohydrates can help. Small swaps add up: replace processed snacks with fruit and nuts; cook with olive oil instead of butter; build plates around vegetables and protein. For broader nutrition themes in diabetes care, see Diabetes for evidence-based articles and diet considerations.

Tip: Consistency beats perfection. Plan simple, repeatable meals, and use batch cooking. Add beverages without added sugars, and watch portion sizes mindfully. These steps support glucose targets and downstream lipid signaling.

Exercise: Benefits, Risks, and Practical Targets

Regular movement improves insulin sensitivity by activating muscle glucose uptake. Aerobic training and resistance work both help, and together may be best for many adults. Importantly, training should be individualized around joint health, fitness level, and complications like neuropathy or retinopathy. Brief, frequent bouts can be as helpful as longer sessions for beginners.

Clinicians often explain how does exercise help type 2 diabetes by highlighting improved insulin action, muscle growth, and reduced visceral fat. Adults should aim for weekly aerobic and muscle-strengthening targets as tolerated. For neutral guidance on activity targets, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention outline activity guidelines for adults that you can adapt with your care team. For broader disease context, see Type 2 Diabetes for related education and management topics.

Note: Some activities may not suit specific complications. High-impact moves can worsen neuropathic foot risk or aggravate retinopathy. Choose low-impact options like cycling, swimming, or brisk walking when needed, and use properly fitted footwear and glucose monitoring.

Supplements and Emerging Therapies

Many products claim to modify lipid pathways, but evidence varies. Omega-3s, soluble fiber, and plant sterols may support lipid profiles generally; always review safety and interactions with your clinician. Some teams are studying supplements to reduce ceramides, yet protocols and outcomes are still maturing. Focus first on diet, activity, sleep, and weight management, which have stronger and broader evidence.

Glucose-lowering medicines can indirectly influence lipid signaling by improving glycemia and weight. For context on metformin formulations often used in type 2 diabetes, see Glumetza for an overview of extended-release metformin. For combination metformin plus DPP-4 therapy, see Janumet XR as a background example used in practice. For SGLT2 therapy that supports glycemic control and cardiorenal outcomes, see Dapagliflozin for class context and indications discussed on-label.

Incretin-based therapies are under active study for weight and metabolic markers. For heart-related outcomes of a GLP-1/GIP agent, see Mounjaro Heart Benefits for emerging cardiometabolic insights. If you use injectable incretin medicines, proper device handling matters; for needle basics, see What Are BD Needles for safe technique guidance. Storage also protects potency; for an example, see Zepbound Storage for general cold-chain handling principles.

Clinical Testing, Synthesis Pathways, and Biomarkers

Laboratories can quantify ceramide species using mass spectrometry. Panels sometimes aggregate results into risk scores. These scores may aid risk stratification in research and select clinical settings. Reference ranges differ by lab, and population norms are evolving.

Pathway-wise, ceramide synthesis involves de novo production, sphingomyelinase-mediated generation, and salvage routes. Enzymes like serine palmitoyltransferase begin the de novo pathway; downstream steps add, remove, or remodel fatty acids. Clinically, these pathways intersect with inflammation, lipoprotein metabolism, and organ-specific stress. In diabetic kidney disease discussions, see Kerendia as a therapy example used to address cardiorenal risk in appropriate patients.

Practical Plan: Steps To Lower Risk

If you want to know how to reduce ceramides in your body, start with consistent fundamentals. Build a plant-forward eating pattern with adequate protein and unsaturated fats. Train both aerobic capacity and muscle strength, adjusting for complications. Sleep seven to nine hours, and manage stress with brief, daily practices like breathing or walks.

Work with your clinician to monitor glucose, blood pressure, and lipids. Track body weight and waist size, and watch for patterns during life changes. Consider whether medication adjustments or nutrition counseling would help you reach safer targets. Revisit your plan every 8–12 weeks, keeping changes small and sustainable.

Recap

Ceramides are bioactive lipids that can influence insulin signaling and metabolic risk. Practical, routine habits—diet quality, movement, sleep, and weight management—support healthier signaling. Medications and select supplements may help as adjuncts when appropriate. Use testing thoughtfully and review changes with your healthcare professional.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice.